Covering something rotten in the state of Denmark

Eight months. That's how long it took to go from being a free man to a life sentence for Peter Madsen, the Danish submarine builder convicted of murdering Swedish journalist Kim Wall. An eight-month gruelling legal epic, during which journalists covering the trial had to struggle to keep their own personal convictions on the question of guilt in check. And yet…

The images were seen around the world: a man in an army-green jumpsuit, stocky and dishevelled, rescued just in the nick of time as his submarine sank to the bottom of a bay off Copenhagen on the morning of August 11, 2017.

Peter Madsen's unflinching face betrays nothing of the crime he has just committed. Apart, that is, from a barely visible drop of blood under his nostrils -- blood that belongs to his victim Kim Wall, a young Swedish journalist who sailed off with him the night before to interview him on board his homemade submarine the UC3 Nautilus, an 18-metre (60-foot) steel craft he designed and built together with a group of enthusiasts.

Eight months later, Wednesday, April 25th. Copenhagen district court judge Anette Burko and two lay judges sentence Madsen to life in prison, Denmark's harshest sentence. It's one that is rarely handed down, with only 25 inmates currently serving life terms. But normally, it's not really for life -- on average, inmates given life terms in the Scandinavian country stay behind bars for 16 years. In Madsen's case, it will probably be much longer than that.

The court found him guilty of premeditated murder, aggravated sexual assault and desecration of a corpse. He had chopped off Wall's head, legs and arms and spread them at sea, weighed down in separate plastic bags with metal pipes. Special Swedish sniffer dogs trained to find bodies lying at depths of up to 30 metres helped divers recover all of her remains.

At the opening of Madsen's trial on March 8, dozens of Danish and foreign journalists throng the courthouse for what is widely considered the country's most sensational criminal case. AFP sends one text and one video reporter. Over the coming weeks, journalists from the Stockholm bureau take turns covering the proceedings.

Housed in an old, imposing building, the courtroom is small and packed. Twelve spots have been reserved for the Danish press, two for the Swedish press, and six for other media who queue for long hours overnight to get a spot on a "first come, first served" basis.

In order to work in the best possible conditions, AFP secures seats in a nearby room where the proceedings are transmitted live on large flat screens. While taking notes and updating articles, the reporters can watch Madsen and hear his sharp-tongued responses. To the psychiatrists who evaluated him and asked him why, if Wall's death was an accident, did he dismember her rather than calling authorities for help, he replied: "When you're faced with a big problem, you break it up into parts."

Journalists who cover a criminal trial are not supposed to be judges. They're not following the case to have an opinion on the question of guilt. But after following the case as closely as they do, it's almost impossible not to. It's hard to ignore that gut feeling.

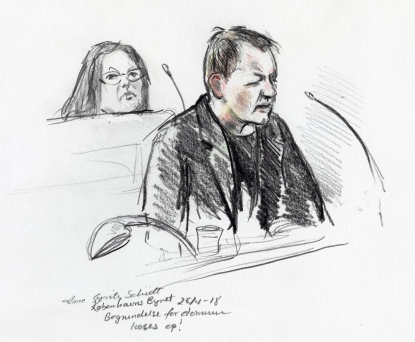

A court drawing of Peter Madsen (right) during his trial in Copenhagen on April 25, 2018. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Anne Gyrite Schuett)

A court drawing of Peter Madsen (right) during his trial in Copenhagen on April 25, 2018. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Anne Gyrite Schuett)In the first hours after his arrest on August 11, Madsen is filmed by a television crew as he is brought onto dry land after his rescue, and it rapidly becomes clear a crime has occurred. A semi-celebrity in Denmark, known for his love of exploring space and sea, Madsen tells reporters at the scene that he barely remembers Wall's first name.

"My passion is finding ways to travel to worlds beyond the well-known," Madsen wrote on the website of his now-defunct Rocket Madsen Space Lab, with which he succesfully launched a rocket eight kilometers into the atmosphere and with which he hoped to one day be the first amateur to travel into space in his own rocket.

He likes to test the limits. Break boundaries. Escape the "real world".

In August 2017, as Wall's body parts begin turning up and it becomes clear something gruesome has happened to her, journalists, AFP included, are quick to draw parallels to the popular Swedish-Danish television crime thriller The Bridge: a Dane, a Swede, a body found in the waters dividing the two countries not far from the Oresund Bridge for which the TV series is named.

Media the world over compare the case to a grisly Nordic noir or a Nordic thriller.

And then the comparisons stop.

A picture taken on April 25, 2018 shows a detail of the homemade submarine UC3 Nautilus as it is covered with green tarpaulin in Copenhagen, Denmark. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Mads Claus Rasmussen)

A picture taken on April 25, 2018 shows a detail of the homemade submarine UC3 Nautilus as it is covered with green tarpaulin in Copenhagen, Denmark. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Mads Claus Rasmussen)Because it's too close to reality. And it could have happened anywhere.

Yet what is shocking in this particular case is the contrast between the brutal violence committed against Wall -- a young, adventurous reporter -- and Scandinavia's reputation as a safe place with a good standard of living, where Danes top the UN's rankings as the happiest people in the world.

What shocks are the last pictures taken of Wall the night she left for a sail with Madsen, photos taken by passing boaters where she stands in the sub tower wearing a bright orange top in the sunset, smiling innocently just hours before her death, completely unsuspecting of the events to come. That smiling face, contrasted with the circumstances -- at the time still piecemeal -- of her death.

There is no cultural or sociological explanation for this crime. It is purely a human interest story. A tragic one.

Ingrid Wall and Joachim Wall, parents of murder victim Kim Wall, are interviewed at the inaugural grant ceremony for The Kim Wall Memorial Fund at Superfine on March 23, 2018 in New York City. (AFP / Angela Weiss)

Ingrid Wall and Joachim Wall, parents of murder victim Kim Wall, are interviewed at the inaugural grant ceremony for The Kim Wall Memorial Fund at Superfine on March 23, 2018 in New York City. (AFP / Angela Weiss)The only witnesses to the events of that night are the refloated submarine, its captain and the victim's body. The entire investigation -- and the ensuing trial -- will rely on whatever information can be gleaned from those three.

And that makes it tough for the judges. There is no irrefutable tangible evidence in the case. Instead, it is based largely on the accused's profile and character.

A guilty verdict is supposed to be based on hard evidence -- prosecutors know they must prove Madsen's guilt beyond any reasonable doubt. If there is any doubt, Madsen could walk free -- as his defence lawyer, Betina Hald Engmark, hammers throughout the trial, her first ever homicide case.

Yet for those who have followed the case since the beginning, it becomes increasingly clear that as much as proving that Madsen tied Wall up, beat her, sexually mutilated her and either slit her throat or strangled her, the prosecution's strategy is to prove that no other scenario is plausible, and that Madsen's claim that it was all an accident cannot possibly be true.

Court drawing of Peter Madsen (left) during his trial at the courthouse in Copenhagen, April 25, 2018. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Anne Gyrite Schuett)

Court drawing of Peter Madsen (left) during his trial at the courthouse in Copenhagen, April 25, 2018. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Anne Gyrite Schuett)With no irrefutable evidence proving Madsen's guilt, and faced with the possibility that the court could acquit him on one or several of the charges, prosecutor Jakob Buch-Jepsen urges the judges to use their "common sense".

Madsen knows the prosecution lacks hard evidence. Testifying at one point, he told the prosecutor: "Jakob, I won't say anything until the material evidence you present requires me to."

The case is full of objective elements and circumstantial evidence. But is it enough to prove Madsen's guilt?

The court decided so. But in the Danish press, legal experts had since the opening of the trial raised the possibility that he could be acquitted of the charge of premeditated murder and aggravated sexual assault. Madsen would in such case have only been convicted of desecrating a corpse -- which he had admitted -- a crime punishable by six months in prison.

The journalists in the Stockholm bureau were not 100 percent sure he would be convicted, but, truth be told, we were pretty convinced of his guilt as soon as he told his first lie to investigators. I'm the first to admit it. It's a gut feeling, but also a gamble. And, as horrible as it may sound in such a macabre case, an intellectual game: Am I right? Am I wrong?

Members of the media set up in front of the courthouse in Copenhagen, on April 25, 2018. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Mads Claus Rasmussen)

Members of the media set up in front of the courthouse in Copenhagen, on April 25, 2018. (AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Mads Claus Rasmussen)As we write our articles covering the trial, we remain committed to describing a man presumed innocent but accused of a murder most foul. But, as the investigation progresses and more details of the case emerge, the question marks in our stories gradually disappear.

In August 2017, we write a profile describing him as an "eccentric inventor" -- not a murderer. In March 2018, our profile says he's an "eccentric 'inventrepreneur' portrayed by the prosecution as a sexual sadist", and then, after the verdict is handed down, he is "a dark inventor turned murderer (with) macabre fantasies involving violent sex, beheaded women and snuff films".

Each word is weighed carefully to ensure we're not judging him, and to give balanced coverage of both the prosecution's and the defense's arguments.

Let's look at the objective elements in the case first: Madsen was alone on the sub with Wall on the night of August 10. Wall died on board, Madsen admits that. He also admits dismembering her, cutting off her head, arms and legs with tools he refuses to disclose. He stabs her torso and her genital area with an extra-long, sharpened screwdriver -- in order to prevent gases from building up inside her torso which would have prevented her from sinking to the seabed, he claims.

Madsen explains he threw her body overboard, in Koge Bay off Copenhagen, to give her a sea burial.

Then there are the objective elements contested by the defense: the fact that Madsen brought objects on board the vessel that were unnecessary for a submarine, such as plastic luggage strips, a wood saw, metal pipes, and the extra-long sharpened screwdriver. According to the prosecution they were used to commit the crime, and a sign of premeditation.

The autopsy ruled out one of Madsen's versions of how Wall died -- that the heavy hatch door fell on her head, killing her -- because no blunt trauma was found on her skull. It also found 14 stab wounds in and around her genitals, and concluded that her lungs showed signs of mechanical asphyxsia, either by strangling or a slit throat. Madsen then claimed she died when toxic fumes filled the sub while he was up on deck, when the hatch door fell shut and couldn't be opened because of a vacuum effect.

Defense attorney Betina Hald Engmark arrives at the Copenhagen City Court on March 28, 2018.

(AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Mads Claus Rasmussen)

Defense attorney Betina Hald Engmark arrives at the Copenhagen City Court on March 28, 2018.

(AFP / Ritzau Scanpix/ Mads Claus Rasmussen)His defense managed to sow doubt over the autopsy report during the coroner's testimony: Could it have been carbon monoxide poisoning? Not completely impossible, she admitted, noting the torso's decomposed state after submersion in water for 10 days. Did the neck show signs of being slit? Not impossible, but not certain either. Were the stab wounds to the genital area inflicted before or after death? Impossible to determine with 100 percent certainty, except one which occurred at the time of death or just after.

And then there are the subjective elements: Madsen's hard drive, seized in his workshop, and testimony from those who know him, suggest he has macabre, sado-masochistic passions. Experts diagnose him as a "perverse polymorph" with "psychopathic traits". The court views several insufferable video clips found on the hard drive -- including his own sexual encounters where he wears a GoPro camera on his forehead -- and others in which real women and animated figures are tortured, raped, impaled, skinned, and beheaded. The films are so gory only the defence, the prosecution and the judges are allowed to view them, as the screens are turned away from the rest of the courtroom. The investigation also reveals Madsen searched the internet for videos of beheadings of women, just hours before Wall's death.

At one point during the trial, text messages Madsen sent to a woman friend on August 4 are projected onto the screen. The defense protests, but the court allows it.

Her: "Can you send me death threats?

Him: "I'll tie you up and stab you with a skewer... I take a knife and look at your throat, at the spot where your carotid artery is. I'll tie you up in the Nautilus."

Circumstantial? Coincidence, Madsen argues. "Jakob," as he calls the prosecutor, "if you watch a movie about a nuclear bomb and a few days later a nuclear bomb explodes, wouldn't that be a coincidence?".

"I'm not on trial," the prosecutor replies.

Madsen meanwhile ramps up his defense: the incriminating hard drive has been lying around his workshop where many people had access to it. He even lent it to an intern and a female friend photographer who's into gory films.

Another witness testifies that Madsen talked about wanting to commit the perfect crime...

Submarine experts reject Madsen's accidental fumes theory, he changes his version of events each time the investigation rules out his account, the psychiatric evaluation of him is damning, but how much will all that matter in the end to the court? The burden of proof lies with the prosecutor, who has little tangible evidence in this case.

In Denmark, a district court is usually made up of three professional judges and six lay judges. But defendants are allowed to reduce that to one professional judge and two lay judges. That's what Madsen and his lawyer choose. Danish media speculate that by eliminating four of his peers, Madsen hopes to limit the role that emotion, common sense and personal conviction will play in determining the verdict, and gambles that the professional judge -- whose vote counts for one-third -- will rely on facts and hard evidence.

The strategy fails. He is found guilty.

On May 7, Madsen appeals the life sentence, but not the guilty verdict.

The inaugural ceremony for The Kim Wall Memorial Fund at Superfine on March 23, 2018 in New York City.

(AFP / Angela Weiss)

The inaugural ceremony for The Kim Wall Memorial Fund at Superfine on March 23, 2018 in New York City.

(AFP / Angela Weiss)