Baghdad tries Islamic State

Baghdad -- One swears he sold chickens in Syria; another that he was a doctor, not a killer; a third that he was kicked out of the Islamic State jihadist group because he was too lazy; a fourth that he managed to get a salary as a fighter without actually doing anything.

But the stories of these Frenchmen who had traveled to the Middle East to join the IS extremists don’t seem to move the Iraqi judge hearing them in Baghdad.

One by one, he condemns the men to death.

This updated combination of file photographs obtained on May 29, 2019, shows eight French nationals who have so far been sentenced to death by a Baghdad tribunal for membership in the Islamic State jihadist group. (from top left to bottom right) Vianney Ouraghi, Salim Machou, Mustapha Merzoughi, Brahim Nejara, Fodil Tahar Aouidate, Kevin Gonot, Yassine Sakkam and Leonard Lopez).

(AFP / -)

This updated combination of file photographs obtained on May 29, 2019, shows eight French nationals who have so far been sentenced to death by a Baghdad tribunal for membership in the Islamic State jihadist group. (from top left to bottom right) Vianney Ouraghi, Salim Machou, Mustapha Merzoughi, Brahim Nejara, Fodil Tahar Aouidate, Kevin Gonot, Yassine Sakkam and Leonard Lopez).

(AFP / -)I had come to cover these trials because Westerners joining IS have always elicited enormous interest in their home countries. The 11 Frenchmen transferred to Iraqi custody from Syria in January were among the first foreigners to be sent to Iraq to be put on trial for membership of IS, a group that sowed terror across Iraq and Syria for years before finally being defeated several months ago. So there was much interest in the fate of these men, both in France and elsewhere, and each time one was due to appear my AFP colleagues and I came to the courthouse to cover the proceedings.

As I made my way to the courtroom, I would pass by Iraqi defendants who, unlike the foreigners, were often trailed by their mothers and wives, the women's faces wet from tears and contorted in pain.

A picture taken on April 29, 2018 in the Iraqi capital Baghdad's Central Criminal Court shows Russian women who have been sentenced to life in prison on grounds of joining the Islamic State (IS) group standing with children in a hallway. Iraq sentenced 19 Russian women to life in prison for joining IS group on April 29.

(AFP / Ammar Karim)

A picture taken on April 29, 2018 in the Iraqi capital Baghdad's Central Criminal Court shows Russian women who have been sentenced to life in prison on grounds of joining the Islamic State (IS) group standing with children in a hallway. Iraq sentenced 19 Russian women to life in prison for joining IS group on April 29.

(AFP / Ammar Karim)I would stand half a meter away from the men during their time in court -- the only thing between us were the wooden pillars of the defendants’ box. Dressed in ill-fitting yellow uniforms and plastic sandals they all tried to defend themselves before listening impassively to the verdict.

“Death by hanging,” Judge Ahmad Mohammad Ali would say again and again.

Then they were escorted by police out of the courtroom, sometimes shoving a journalist or a lawyer on their way out.

In court they appeared with their heads and beards shaven. But I still recognized them, having scrutinized photos distributed by IS’s formidable propaganda machine or by French and Iraqi intelligence services.

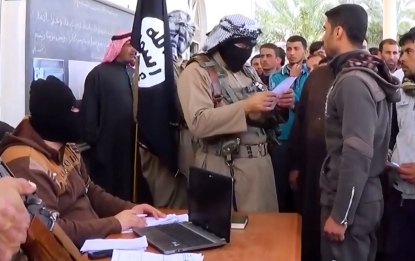

An image grab taken from a propaganda video released on March 17, 2014 by the Islamic State's al-Furqan Media allegedly shows IS fighters displaying the jihadist flag in the Anbar province in Syria.

(AFP / -)

An image grab taken from a propaganda video released on March 17, 2014 by the Islamic State's al-Furqan Media allegedly shows IS fighters displaying the jihadist flag in the Anbar province in Syria.

(AFP / -)These were the men who at one time, sent shockwaves around the world with videos of executions, or photos of them posing in front of people they killed or with their weapons in the desert. Taking advantage of a power vacuum in Syria and Iraq, the IS swept across the region to establish a “caliphate” and at the height of its power controlled the lives of millions of people in a landmass roughly the size of the United Kingdom.

The men in the defendants’ box in the Baghdad courtroom were a far cry from the ones posing in those videos. Even though every once in a while, some would glare fiercely as the charges against them were read out.

Some of them were accused of serving as members of the “Islamic police,” with the power of life and death over millions of people. In videos, tweets and other social media posts, they encouraged their countrymen to join them in their “caliphate,” where people were decapitated and their heads sometimes stuck on spikes in the center of town, where people were stoned in public for disobeying the strict form of Islamic law that IS imposed. Some of them appeared in footage specifically addressing France’s youth, using a mix of rap and Muslim religious chants called anasheed to vow death to all who didn’t join them.

A member of the Yazidi minority searches for clues on February 3, 2015, that might lead her to missing relatives in the remains of people killed by the Islamic State (IS) jihadist group, a day after Kurdish forces discovered a mass grave near the Iraqi village of Sinuni in the Sinjar region.

(AFP / Safin Hamed)

A member of the Yazidi minority searches for clues on February 3, 2015, that might lead her to missing relatives in the remains of people killed by the Islamic State (IS) jihadist group, a day after Kurdish forces discovered a mass grave near the Iraqi village of Sinuni in the Sinjar region.

(AFP / Safin Hamed)In one such video shown in court, a man chanted:

“It’s a war for eternity”

that will catch up with everyone

“from the Buddha to the Trinity”

In the background, images flickered of the Bamiyan Buddhas destroyed by the Taliban in Afghanistan and of Pope Francis.

“The Jews will get what they deserve,” went another refrain over images of US President Donald Trump shaking hands with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

An image grab taken from a propaganda video released on March 17, 2014 by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)'s al-Furqan Media allegedly shows ISIL fighters recruiting volunteers at an undisclosed location in the Anbar province. (AFP / -)

An image grab taken from a propaganda video released on March 17, 2014 by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)'s al-Furqan Media allegedly shows ISIL fighters recruiting volunteers at an undisclosed location in the Anbar province. (AFP / -)The accused mostly watched these videos impassively. When the judge asked them to point themselves out, some leaned forward, staring hard, as if seeing the images for the first time.

In a hurried mix of Arabic and French, they tried to defend themselves to the judge – some with a shrill tone and others speaking low, a few muttering a short excuse and others spewing forth arguments.

Some still boasted. “I don’t need IS money,” Fodil Tahar Aouidate told the judge after the latter mentioned the salary he received when he worked in IS’s military administration. “My sisters sent me money, they’re even going to go to prison for it.”

Two of his sisters had been found guilty in France of financing terrorism for sending some 15,000 euros to Syria, including government “family allowance” financial aid that the French state distributes to all families with at least two children and that their relatives continued to receive after leaving the country to join IS.

Others claimed they had repented. Like Mustapha Merzoughi, who asked the judge to send him back to France “to help battle against terrorism.”

An Iraqi man cries over body-bags containing the remains of people believed to have been slain by jihadists of the Islamic State (IS) group lie on the ground at the Speicher camp in the Iraqi city of Tikrit, on April 12, 2015. (AFP / Ahmad Al-Rubaye)

An Iraqi man cries over body-bags containing the remains of people believed to have been slain by jihadists of the Islamic State (IS) group lie on the ground at the Speicher camp in the Iraqi city of Tikrit, on April 12, 2015. (AFP / Ahmad Al-Rubaye)When I first set out to cover these trials, I thought I would once again hear the tales of horror I had become accustomed to after several years covering IS in the region.

In Mosul, when the battle to retake the city from the IS began in October 2016, I saw the first families flee the city carrying white flags above their heads, full of chilling stories of the years they spent living under the jihadists.

When I went to the Iraqi city of Hawija the day it was retaken from the jihadists, I saw signs still promising death to smokers and leaflets extolling the benefits of martyrdom.

I met countless mothers and fathers who hadn’t heard from their husbands or sons -- who probably lay buried in a mass grave somewhere after having been summarily executed by IS. I listened to children tell me, with the vocabulary and matter-of-fact tone of adults, about their parents’ terror and helplessness in the face of the jihadists.

Iraqi families walk down a road as they flee Mosul on March 3, 2017, during an offensive by security forces to retake the western parts of the city from Islamic State (IS) group.

(AFP / Aris Messinis)

Iraqi families walk down a road as they flee Mosul on March 3, 2017, during an offensive by security forces to retake the western parts of the city from Islamic State (IS) group.

(AFP / Aris Messinis)One of IS’s most shocking acts -- the use of sex slaves, particularly from the Yazidi minority -- did come up in the Baghdad court.

When one of the accused, Yassin Sakkam, mentioned a “slave market,” the judge asked him to provide more details.

“There was one in Deir Ezzor” in Syria,” Sakkam said matter-of-factly. “That’s the one that was known among the foreigners.”

In August 2014, the IS overran the area of Sinjar, which was inhabited mostly by the Yazidi minority whom the jihadists considered heretics. Thousands of men are believed to have been killed in the IS campaign against the Yazidis, while thousands of women and girls were sold to IS fighters as sex slaves. One German woman who had traveled to Syria went on trial in April for letting a young Yazidi girl that she and her husband “bought” die of thirst.

Yazidi women and children rescued in Iraq in the village of Qizlajokh, April 13, 2019. (AFP / Delil Souleiman)

Yazidi women and children rescued in Iraq in the village of Qizlajokh, April 13, 2019. (AFP / Delil Souleiman)But aside from the mention of the Yazidis, there was no examination of IS crimes in the Baghdad courtrooms. The horror of IS crimes, the fate of their victims, determining death tolls and measuring the damage wrought by the group were left for another day, another place. A proper process would mean identifying the victims of more than 200 mass graves, discovering the fate of some 3,000 Yazidis who still remain missing and detailing the horrors inflicted by the jihadists on the population they once controlled.

Graphic photos

A picture taken on January 20, 2017, shows a dead body hanging from an electricity post in eastern Mosul during an ongoing military operation against Islamic State (IS) group jihadists. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

A picture taken on January 20, 2017, shows a dead body hanging from an electricity post in eastern Mosul during an ongoing military operation against Islamic State (IS) group jihadists. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff) An image grab taken from a propaganda video released on March 17, 2014 by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)'s al-Furqan Media allegedly shows ISIL fighters executing a man at an undisclosed location in the Iraqi Anbar province. (AFP / -)

An image grab taken from a propaganda video released on March 17, 2014 by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)'s al-Furqan Media allegedly shows ISIL fighters executing a man at an undisclosed location in the Iraqi Anbar province. (AFP / -) An image grab taken from a video uploaded on social networks on August 28, 2014, shows young men in underwear lying on the ground after being allegedly executed on August 27, 2014 by Islamic State (IS) militants at an undisclosed location in Syria's Raqa.

(AFP / -)

An image grab taken from a video uploaded on social networks on August 28, 2014, shows young men in underwear lying on the ground after being allegedly executed on August 27, 2014 by Islamic State (IS) militants at an undisclosed location in Syria's Raqa.

(AFP / -) A handout photo by the Iraqi justice ministry shows Islamic State jihadists awaiting their execution after being convicted and sentenced to death, June 29, 2018.

(AFP / Handout)

A handout photo by the Iraqi justice ministry shows Islamic State jihadists awaiting their execution after being convicted and sentenced to death, June 29, 2018.

(AFP / Handout) A handout picture released by the Iraqi justice ministry on June 29, 2018 shows the execution by hanging of jihadists of the Islamic State group who were on death row. (AFP / Handout)

A handout picture released by the Iraqi justice ministry on June 29, 2018 shows the execution by hanging of jihadists of the Islamic State group who were on death row. (AFP / Handout)

But this is not the goal of the Baghdad trials. Their goal is simply to establish whether the defendants belonged to IS. For IS is classified as a terrorist group and membership of a terrorism group is enough to get the death penalty under Iraqi law.

I remember the first time this struck me. It was in August 2018, when I covered the trial of Lahcene Gueboudj, a 58-year-old plumber from the southern French city of Toulon who was accused of joining IS. He swore he had been captured in Syria and transferred to Iraq by American forces, while the judge insisted he had been captured in Mosul. At the time, I couldn’t figure out which was the truth. His trial lasted half an hour. He was handed a life sentence. I later learned that the man had been right all along -- he was captured in Syria and transferred to Iraq.

French jihadist Djamila Boutoutaou attends her trial at the Central penal Court in Baghdad, on April 17, 2018. She was sentenced to life in prison for membership in the IS. (AFP / Ammar Karim)

French jihadist Djamila Boutoutaou attends her trial at the Central penal Court in Baghdad, on April 17, 2018. She was sentenced to life in prison for membership in the IS. (AFP / Ammar Karim)Back then, it seemed unlikely that Iraq would try foreigners for crimes allegedly committed outside of its territory. But in recent months, it seems Baghdad is preparing itself for more such trials -- few foreign countries have been enthusiastic about taking back its nationals who had joined IS and Iraqi government sources have told us that Baghdad has offered to try hundreds of foreign IS suspects who had been detained in Syria. In return, the sources have said, Baghdad has asked for two million dollars per prisoner -- the reported cost of maintaining a prisoner in the American Guantanamo prison. It is not clear if any countries will accept such an offer and if they do, they’re unlikely to confirm so officially. So far, few countries have taken their nationals back to try on home soil.

The 11 Frenchmen who have been judged so far have had some two hours to plead their case in front of a courtroom full of journalists and diplomats. Before them, thousands of Iraqis and hundreds of foreigners who had been accused of joining the IS passed before the same judges.

Their trials lasted for a few minutes before most of them got a death or a life sentence. But no-one was there to record exactly what had happened.

Men suspected of being Islamic State (IS) fighters carry a wounded man as they walk toward the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) after leaving the IS group's last holdout of Baghouz in Syria's northern Deir Ezzor province on February 22, 2019.

(AFP / Bulent Kilic)

Men suspected of being Islamic State (IS) fighters carry a wounded man as they walk toward the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) after leaving the IS group's last holdout of Baghouz in Syria's northern Deir Ezzor province on February 22, 2019.

(AFP / Bulent Kilic)