Twitter and news agencies: BFF or frenemies?

(AFP Photo / Odd Andersen)

PARIS, March 31, 2015 - Here, then, the tortuous (no, I did not say ‘torturous’) saga of how Agence France-Presse and Twitter tied the knot, paving the way for AFP to make and market a novel news service situated somewhere near the crossroads of Social Network Ave. and News Agency Blvd.

The three-year road trip leading to AFP TweetApps – from garage prototype to full-strength industrial product – was strewn with speed bumps, detours and dead ends, and there will be other obstacles ahead. Nature of the game. What makes the story worth telling, however, are the issues we confronted along the way: the uncertain news media-social network chemistry, the blurry boundary between journalism and ‘curation’, and all the ways in which a 180-year old news mastodon is not a startup.

From 'print' to 'dot.com' to 'search' to 'social'

A lot of (mostly virtual) ink has been spilt on the looming threat of Twitter to so-called ‘legacy’ news media. Agencies such as AFP, Reuters and the Associated Press (AP) – global wholesalers that gather and sell content to other media – were said to be especially vulnerable to the 500+ million mini-messages that course through Twitter every day, blanketing the planet on every subject imaginable.

The Paris headquarters of AFP's ancestor, the Press Agency Havas, in 1922 (AFP Photo)

The Paris headquarters of AFP's ancestor, the Press Agency Havas, in 1922 (AFP Photo)The bottom-line question is summed up nicely by the title of a 2013 academic paper published by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: “Can Twitter replace Newswire for breaking news?” Dinosaur-like agencies “must evolve or meet extinction”, Reuters’ then-social media editor Anthony De Rosa warned about the same time: “To bury our head in the sand and act like Twitter isn’t increasingly becoming the source of what informs people in real-time is ridiculous.” Facebook, too, is seen to be driving the news business’s inexorable migration from 'print' to 'dot.com' to 'search' to 'social'.

Extracting value from the roiling torrent

At first glance, Twitter does indeed look like a competitor. News agencies have historically offered their clients two things: speed and accuracy. But for most breaking stories today – a suicide attack, a plane crash, a summit meeting – tweets provide sometimes crucial information not only before the dust has settled but while it is still rising in the air. Unless one of its reporters happens to be on the scene, no news outfit can be faster on the draw than that.

But here’s where De Rosa gets it wrong: Twitter is not a news-gathering organization, but an unfiltered conduit where a quarter of a billion active users rant and ramble, argue and allege, report and distort. And let’s face it, much of what they have to say is just not that interesting. Or accurate, and that’s the point: the world still needs professional news handlers – more-or-less tethered to a code of ethics – to help vet, verify and explain what’s going on around us.

An England fan takes a smartphone picture during a World Cup 2014 qualifying match against Poland in London in 2013

(AFP Photo / Adrian Dennis)

Like all news organizations, AFP has learned to exploit Twitter to monitor events, find sources, build networks, and broadcast our production on dedicated feeds. We also do with tweets what journalists have always done: fact-check, verify, exercise our news judgment as to what is worth highlighting (or not). But in 2012, we set up an experiment to see how we might extract even more value from the roiling torrent flowing through Twitter’s so-called ‘firehose’, passing it on to our media clients and, ultimately, the news consumer.

Collecting the nuggets

Digging for gold, one has to sift through a lot of dirt and debris before collecting the nuggets. When it comes to Twitter, the most common approach to ‘data mining’ is to use mathematical formulas called algorithms. AFP added a journalistic layer: creating and maintaining a ‘Who’s Who’ database of hand-selected Twitter accounts related to a particular topic, a qualitative process that computers can’t quite pull off (yet!). Our goal was simple: if 9 out of 10 Tweets generated by a keyword search in Twitter on a top news story – think World Cup final or Israeli election – are not worth reading, we wanted to build a system that would reverse that ratio.

E-diplomacy co-developers Marlowe Hood (front) and Joan Tilouine (AFP Photo)

E-diplomacy co-developers Marlowe Hood (front) and Joan Tilouine (AFP Photo)The result, published in 2012, was the e-diplomacy hub, a Web application sitting on top of the 5,000 most influential Twitter accounts in international relations we could find, from presidents and diplomats, to experts and NGOs, to hactivists and, quarantined from the rest, terrorist organizations. The accounts were collected by AFP’s global network of journalists and vetted by a team of developers in Paris. The Hub was not a product but – to use a bit of jargon – a ‘proof of concept’ that would allow us find out if it was technically, editorially and commercially viable.

Two reactions in particular convinced me that we were on the right track.

About three months after we launched the e-diplomacy hub, I noticed (thank you Google Analytics) that our #1 user was the US State Department. I expected the public policy folks there to have a look-see, but they were consulting the platform every day. Why? Surely if there was one institution with tools that would put our modest application – pieced together by three journalists, a freelance programmer and a graphic artist moonlighting from her day job – to shame, it would be the State Department. But when I met with them a few months later, they explained that they had nothing of the kind.

(AFP Photo / Leon Neal)

(AFP Photo / Leon Neal)The second bit of feedback, which eventually led to our signing an agreement, was from Twitter itself. Discussions between AFP and the San Francisco-based company had just begun, and in one meeting our 20-something interlocutor suddenly looked up and said: “I get it. You guys are doing exactly the opposite of what we do.” By that he meant that we had a qualitative, journalistic approach to cherry-picking content that Twitter could not easily duplicate.

Twitter evangelists

But if Twitter was eager from the get-go for us to extend the concept into a product line, some of my colleagues at AFP were not. And they raised a valid question: Is this journalism? What business does a news agency have repackaging tweets?

And so it was that I joined the ranks of the Twitter evangelists within the Agency. A strange turn of events because, until I embarked on this adventure, I was an old-school reporter covering topics ranging from particle physics to climate change. I’ve never tweeted very much, and still don’t. Not my thing. But I do recognize the power of the platform, and the hugely important role Twitter has come to play in what it is now fashionably called the global media ecosystem. It simply cannot be ignored. Eventually, even my most doubtful colleagues came to agree.

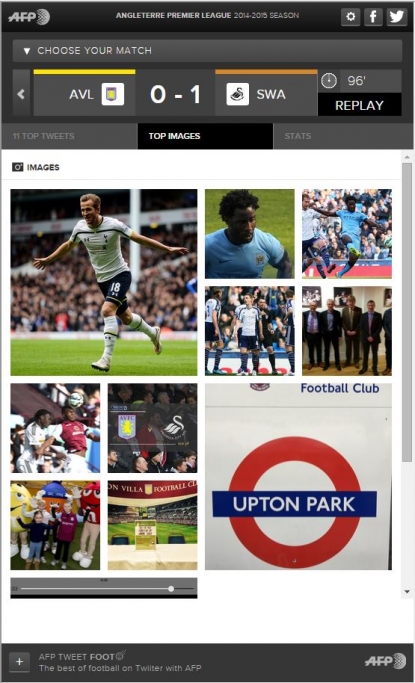

The Tweet Foot application (AFP)

Once the project got a green light from AFP’s CEO, we set about scaling up. Technically, the objective was to create a system for filtering and displaying tweets (and generating stats) that was indifferent to the topic, whether politics, pop music, or pro bowling. Easier said than done: never could I have imagined the distance between prototype and product, or the number of people within AFP that would be involved – engineers, designers, security experts, journalists, marketing folk, client support teams. Nor could we have done it on our own: much of the heavy lifting at the back end was done by engineering firm Zenika, while Web designers at Datagif gave us the look and feel.

Commercially, the aim is… well, to make money, so sports was a no-brainer. Global interest plus our own expertise made European football the obvious place to start.

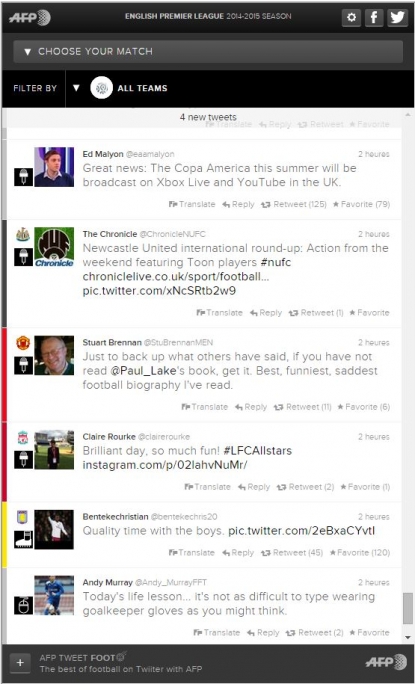

Here’s how it works: the applications for each league sit on top of up to 1,500 hand-picked Twitter accounts. Staying within our traditional role as wholesalers, AFP offers subscribers ‘plug-and-play’ apps ranging in size from Twitter timelines designed for cell phones to full-fledged websites with match-specific timelines along with tweet-based statistics and rankings.

The Tweet Foot application (AFP)

Individual tweets are enriched with information, such as the tweeter’s profile and whether s/he is affiliated with a particular team. We expect a lot of fans to consult them while watching games on TV, sometimes called ‘second screen’ usage. Media clients can also opt to receive the data without the wrapping, and display it within their own templates.

AFP plans to expand its range of Twitter-based applications across other sports, as well as topics ranging from US politics to climate change. But how far we go, of course, will depend on the demand for these platforms, and the ever-shifting sands of the digital infrastructure on which today’s news media is being built.

Journalist Marlowe Hood is the co-creator of ‘the e-diplomacy hub’ and project coordinator for AFP TweetApps. In his last reporting position he covered science, health and environment from 2007 to 2012.