Open House at the CIA

LANGLEY, United States, December 15, 2014 - The fresh-faced staff members scurried back and forth among the rows of chairs, checking the lighting and the flags on a makeshift stage. They were clearly nervous. This had never been done before.

Press conferences may be routine events in Washington, but not at the Central Intelligence Agency. For the first time in its history, the CIA director was holding a live, televised news conference – direct from the spy agency's headquarters in Langley, Virginia.

If anything, this felt more like a wedding, and the hosts were anxious how the guests – who are not part of “the company” – would behave.

The guest list was exclusive to begin with: almost all US nationals. Before the festivities began, CIA employees stood at the building's entrance – the one featured in “Argo” and other Hollywood films – wanting to know if I had a smartphone, laptop or “anything that can transmit.”

Reporters were only allowed digital recorders and notebooks. The NBC television network was handling the live broadcast in a pool arrangement, and a handful of photographers, including Jim Watson of AFP, were permitted to snap pictures.

Each photographer had a CIA minder shadowing them to ensure they refrained from taking any photos of the agency employees sitting in the audience. The minders were “standing behind us and periodically asking to see our pictures on the back of our camera to see what we were getting with different lenses,” Jim said. The television camera had to stay focused on the podium, to ensure CIA officials sitting in the front rows did not appear on screen.

Many of us had been inside the building before, but never in such conditions. For occasional intelligence briefings, a small number of reporters are given access to officials who cannot be quoted by name, and there are no live television feeds.

Flags at Pepperdine University in Malibu honouring the victims of the September 11, 2001 attacks (AFP Photo / Mark Ralston)

Flags at Pepperdine University in Malibu honouring the victims of the September 11, 2001 attacks (AFP Photo / Mark Ralston)US spymaster John Brennan called the news conference two days after a scathing report from the Senate Intelligence Committee, which recounted how the CIA subjected terror suspects to torture and abuse in the years after the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Incredulous reporters couldn't quite believe the event was happening, and nor could some of the CIA employees watching it all unfold.“This a big deal for us,” said one.

Perhaps the agency hoped the white-marble lobby, with the agency's insignia emblazoned on its floor, would inspire an element of awe and restraint among the press corps.The CIA foyer includes a life-size, bronze statue of the man seen as the spy service's founding father, “Wild Bill” Donovan, who masterminded the cloak-and-dagger spy missions of the storied OSS during World War II. On the other side is a memorial wall with 111 stars, each one honoring a CIA officer who died in the line of duty.

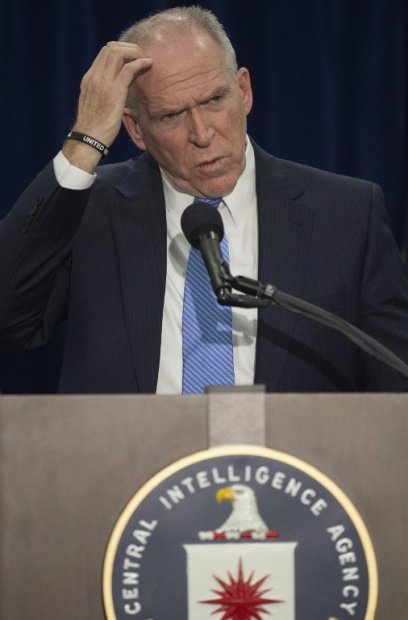

Central Intelligence Agency Director John Brennan at a press conference at CIA headquarters on December 11, 2014 (AFP Photo / Jim Watson)

Central Intelligence Agency Director John Brennan at a press conference at CIA headquarters on December 11, 2014 (AFP Photo / Jim Watson)Unlike a typical press conference at the White House or the State Department, the first few rows were cordoned off for CIA officials. “A buffer zone,” in the words of one journalist.

The Senate report described in excruciating detail the crude torture methods used as CIA officers sought to "break" Al-Qaeda suspects in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks, including waterboarding, hanging people for hours from their wrists and locking them in tiny coffin-shaped boxes.

The CIA had tried to respond to the report and posted material on its website, said spokesman Dean Boyd. "But our view wasn't getting out there," he said. "Brennan "really wanted to speak about the Senate report," he said, and the ground-breaking nature of the press conference guaranteed him global attention.

From the podium, the CIA chief spoke at length in defense of his officers, admitting there had been “abhorrent” abuses in the wake of 9/11, but declining to use the word “torture”.

CIA director John Brennan takes questions from reporters on December 11, 2014 (AFP Photo / Jim Watson)

CIA director John Brennan takes questions from reporters on December 11, 2014 (AFP Photo / Jim Watson)When Brennan stepped off the stage, the CIA staff members looked visibly relieved the event had gone off without a hitch.

There was some history-making for AFP as well, as one of the few foreign media on hand. When I managed to get in a question, it must have been the first time the words “Agence France-Presse” were announced over a microphone in that foyer.

Etched into the wall of the lobby is a passage from the Gospel of St. John: "And ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free."

Judging from my experience at the CIA last week, the world’s most powerful spy agency is not quite ready to share its home truths with the outside world. Allowing news cameras inside its headquarters was strong gesture towards openness – but it was also clear the transparency would only go so far.

After the event my photographer colleague, Jim, had to show all of his photos to his minder. She nixed four of them.

Dan De Luce is an AFP reporter at the Pentagon.

The cover of the Senate Select Committee study of the Central Intelligence Agency's detention and interrogation program

(AFP Photo / US Senate / Handout)

A censored page from the Senate Select Committee study of the Central Intelligence Agency's detention and interrogation program

(AFP Photo / US Senate / Handout)