Asking the right questions in Haiti

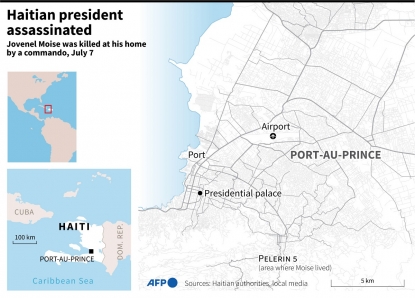

These days, my phone rings off the hook. “Why was Jovenel Moise assassinated?” they all ask in the wake of the brutal slaying of Haiti’s president at his home in Port-au-Prince in the early hours of July 7. “Why” – I often tell foreigners freshly arrived in Haiti to ban that word from their vocabularies. Then, inevitably, they would ask me why they should do that.

And I would repeatedly launch into the explanation: that “why” would lead to a whole load of other questions, that they would not have time to listen, and that the conversation would undoubtedly end with “Haiti is complicated.”

Why does such ignorance about Haiti prevail? The country is effectively missing from French history books. Despite listening to hours of lectures about the Napoleonic wars during my time at university in the French city of Nantes, I never heard the names Toussaint Louverture or Jean-Jacques Dessalines -- heroes of Haiti’s independence movement against France, the colonial power. It’s only when I chose to write my Master’s thesis on the democratic transition crisis in Haiti that I began to learn about it.

That was how I discovered that the idyllic beaches of Haiti that were swamped with high-class tourists in the 1970s were no longer featured in tourist guidebooks – while tourism is all the rage in the Dominican Republic, which makes up the other two-thirds of Hispaniola, the Caribbean island divided between the two nations.

A man walks on a beach close to the the city of Jacmel, 95 km (about 60 miles) south-west of Port-au-Prince, on September 26, 2018. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

A man walks on a beach close to the the city of Jacmel, 95 km (about 60 miles) south-west of Port-au-Prince, on September 26, 2018. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Because contemporary history cannot be learned in books, I decided to head to Port-au-Prince in February 2005 -- my first trip on my own, and my first time out of Europe. It was a crucial trip for me, to attempt to understand the reality of a day-to-day life so different from mine. It was also an essential trip allowing me to talk to the players and witnesses to the political crisis raging at the time. It was the crisis that had brought Haiti back to the front page of newspapers: the ousting from power of president Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Aristide, who once was a priest in the slums, became the country’s first elected leader in 1990. But in February 2004, mass demonstrations and a coup d’etat – which had the backing of France and the United States – cut short his second term in power.

Haitians walk past a billboard of Haitian President Jean Bertrand Aristide on a street 28 February 2004 in Port-Au-Prince, (AFP / Yuri Cortez)

Haitians walk past a billboard of Haitian President Jean Bertrand Aristide on a street 28 February 2004 in Port-Au-Prince, (AFP / Yuri Cortez)

On my first morning in Port-au-Prince, I learned that the difference between life and death can depend on something as insignificant as a minute spent listening to the radio. It was the most efficient way to know the specific streets and areas where the pro-Aristide armed groups were wreaking havoc.

Thousands of Haitian demonstrators run through the Streets of downtown Port-Au-Prince 29 February, 2004 after hearing the news that embattled Haitian President Jean Bertrand Aristide fled the country. (AFP / Jaime Razuri)

Thousands of Haitian demonstrators run through the Streets of downtown Port-Au-Prince 29 February, 2004 after hearing the news that embattled Haitian President Jean Bertrand Aristide fled the country. (AFP / Jaime Razuri)

In Haiti, you have to do whatever it takes to stay alive, to avoid becoming a statistic. From the long unpaved streets in Port-au-Prince where I was staying, you can’t see any houses –they’re all hidden behind the never-ending breeze block walls. You’d better not get out of your car before the gate opens, even if you have to lay on the horn for several minutes till a member of staff opens it – this typical behavior is not a way to abuse the staff, but simply a rational reflex to avoid being kidnapped.

One night, on another radio station, it took less than a second for my young carefree self, raised in France, to comprehend that no, the blasts I’d heard were not fireworks, but gun shots.

Victim of violence in Port-au-Prince, February, 27 2004. (AFP / Roberto Schmidt)

Victim of violence in Port-au-Prince, February, 27 2004. (AFP / Roberto Schmidt)

“Come to my place on Sunday, we’ll talk it over after some soup” : this offer, from historian Michel Hector, is typical of Haitian hospitality, and they are right to be proud of it. He immediately agreed to answer my questions, at his home. The classrooms at the university where he was teaching, which often had no electricity to power the few tiny fans we had to ward off the heat, was far inferior to the shade of his mango tree for sweeping discussions about the crisis in Haiti.

Once the pot of joumou (a Haitian squash-based soup, a true culinary marvel) was empty, the academic and a few of his colleagues spent hours, on several Sundays in a row, teaching me about the key players on the national political stage – which was about as stable as the electricity.

A young man on the roof of his home surveys the neighborhood of Lavale de Bourdon in the commune of Petion Ville in the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince, on May 9, 2017. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

A young man on the roof of his home surveys the neighborhood of Lavale de Bourdon in the commune of Petion Ville in the Haitian capital Port-au-Prince, on May 9, 2017. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

On my first visit to sociologist Laennec Hurbon’s living room, I remember asking if the causes for the lack of socioeconomic development were linked to the absence of law and order. “To ask that question is to have already answered it,” he told me.

The country is seen as one of the most corrupt in the world. Justice is ancient history in Haiti. Today, prisons are massively overcrowded, full of men who are too poor to pay for a lawyer that could or would even want to take their case. Housed in dire conditions, they wait months, sometimes years to see a judge. This special kind of hell is called “long-term preventive detention” in annual human rights reports.

Funnily enough, only in rare cases do people with money end up in prison. They never even get arrested. And they certainly don’t obey the traffic cops, so there is no point investigating them for embezzlement of public funds or possible election fraud. “Depending on whether you are powerful or poor, the court’s judgments will render you white or black,” wrote French poet Jean de La Fontaine, famous for his fables.

Prisoners rest in a cell in Haiti's National Penitentiary in Port-au-Prince, Haiti on August 30, 2019. (AFP / Chandan Khanna)

Prisoners rest in a cell in Haiti's National Penitentiary in Port-au-Prince, Haiti on August 30, 2019. (AFP / Chandan Khanna) A prisoner sits inside Haiti's National Penitentiary in Port-au-Prince, Haiti on August 30, 2019. (AFP / Chandan Khanna)

A prisoner sits inside Haiti's National Penitentiary in Port-au-Prince, Haiti on August 30, 2019. (AFP / Chandan Khanna)

After a month, I returned to France with more than what I needed for my thesis. And I had also found the answer to the question that I figured I might be asked on journalism school entrance exams: where do you see yourself in 10 years?

Easy answer: Foreign correspondent in Haiti. Four months - rather than ten years - after receiving my diploma from the Bordeaux school of journalism, I was back on a flight to Port-au-Prince. This time, without a return ticket.

A street in Petionville, Port-au-Prince, is seen July 13, 2021 in the wake of Haitian President Jovenel Moise's assassination early July 7. - (AFP / Valerie Baeriswyl)

A street in Petionville, Port-au-Prince, is seen July 13, 2021 in the wake of Haitian President Jovenel Moise's assassination early July 7. - (AFP / Valerie Baeriswyl)

My suitcase was stolen before I had even arrived where I was going to stay, but whatever. I still had my backpack with my computer, camera and voice recorder. The date was November 12, 2009. Little did I know that two months later, I would be using the bag as a pillow during many sleepless nights.

January 12. In Haiti, the date doesn’t need to be followed by a year. Everyone knows which year we are talking about – 2010.

That day, the world was forced to remember there is a country called Haiti. At 4:53 pm, the earth shook violently for 35 seconds. A massive earthquake. More than 200,000 people killed.

Those are the numbers. The words? Thinking about describing the indescribable always brings tears to my eyes. Talented Haitian writers such as my friend Yanick Lahens have put the unspeakable down on paper better than I ever could.

Port-au-Prince January 13, 2010. (AFP / Juan Barreto)

Port-au-Prince January 13, 2010. (AFP / Juan Barreto) Port-au-Prince January 14, 2010. (AFP / Julien Tack)

Port-au-Prince January 14, 2010. (AFP / Julien Tack)

The immediate aftermath of January 12 was about Haitians struggling to shift tons of concrete that had fallen on their loved ones, often with nothing more than their hands. The majority of lives saved were those pulled from the rubble in those precious first hours. It would take more than two days for international aid agencies to coordinate relief efforts from the airport tarmac, where a crowd of reporters was arriving from around the world.

After January 12 was also when I became fully aware of my white privilege. In front of the entrance to Port-au-Prince’s general hospital, about 30 Haitians gathered, wanting to bring food to their loved ones being treated in the courtyard (no one who lived through the earthquake could fathom going into a building at that time). Several US soldiers blocked their way. “Back up, back up,” they told them, pushing them back with their machine guns.

(AFP / Jewel Samad)

(AFP / Jewel Samad)

One soldier spotted me and waved me through. I walked forward, bringing with me a desperate nurse who didn’t speak enough English to explain that she was there to work. I coldly informed the soldier, who was even younger than me, who she was. He asked me how he could be sure she was telling the truth.

In the chaos her life had become, the nurse had gone to the trouble of finding her hospital ID badge. I practically yelled at this man, whose eyes were masked by polarized sunglasses. We went in. The soldier didn’t ask what I, a white woman, was doing at the hospital.

A general view of the Presidential Palace, after the earthquake on January 13, 2010. (AFP / Juan Barreto)

A general view of the Presidential Palace, after the earthquake on January 13, 2010. (AFP / Juan Barreto)

Haiti isn’t complicated. You just have to ask the right questions. Why do the tiger masks seen at carnival celebrations in Jacmel have lion manes? Because when you live in this splendid coastal city, why would you want to limit your creativity?

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

(AFP / Hector Retamal) (AFP / Thony Belizaire)

(AFP / Thony Belizaire)

Why is Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, who ruled with an iron fist after the death of his father, “Papa Doc” François, applauded when he returns from exile in a city where his henchmen raped, tortured and killed people for years? Because the majority of young people greeting the procession in Port-au-Prince weren’t born during the age of the tontons macoutes. And they’ve been told the fable of a capital where life was good, without violence and rubbish in the streets.

Jean-Claude Duvalier's wedding, May 27, 1980 (UPI / AFP)

Jean-Claude Duvalier's wedding, May 27, 1980 (UPI / AFP)

Why did private and public institutions think it would be a good move to finance the installation of an outdoor ice rink under the tropical sun? Aaah, Haiti on Ice. French figure skaters Philippe Candeloro and Surya Bonaly showcased at the Port-au-Prince stadium. The event was announced with much fanfare, with huge posters all over town. Of course, it was pushed back so many times we all lost count.

In the end, the rink was set up on the grass. It quickly became an economic and ecological disaster as the generators churned day and night to attempt the impossible because, as the organizer told me, “it’s difficult to get ice to stay frozen under the sun.” The majority of people in Port-au-Prince don’t have electricity. Indecency doesn’t begin to cover it.

Eventually moved into a small gymnasium, Haiti on Ice turned into two shows with little known figure skaters – no Candeloro and Bonaly after all -- and unlimited access to anyone who wanted to try to skate.

Tropical storm in the commune of Les Cayes, Haiti, on October 21, 2016. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Tropical storm in the commune of Les Cayes, Haiti, on October 21, 2016. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Unlike earthquakes, you know a hurricane is coming before it makes landfall, but you don’t always know if it is going to be devastating or not. With each passing hurricane season in the summer and early fall months, I have become more and more addicted to weather apps. I keep an eye on the path of each storm, hoping that Haiti -- so vulnerable to floods due to deforestation -- will be spared.

In 2016, Hurricane Matthew slammed into the country. With my colleague Hector Retamal, I spent long days going up and down the southern coast, to collect eyewitness accounts of those who had lost everything.

Aeral view following the passage of Hurricane Matthew, in Port- Salut, southwest of Port-au-Prince, on October 9, 2016. (AFP / Nicolas Garcia)

Aeral view following the passage of Hurricane Matthew, in Port- Salut, southwest of Port-au-Prince, on October 9, 2016. (AFP / Nicolas Garcia)

One day, we decided to go up in the hills, towards a small village cut off from the rest of the country because a bridge had been swept away. Ignoring the warnings not to cross through the floodwaters, we walked for hours, crossing the mounting river several times. With water up to my waist, holding on to Hector and our guide for dear life so as not to be swept away by the current, I truly asked myself if I hadn’t gone mad.

Petit Goave where a bridge collapsed during the rains of the Hurricane Matthew, southwest of Port-au-Prince, October 5, 2016. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Petit Goave where a bridge collapsed during the rains of the Hurricane Matthew, southwest of Port-au-Prince, October 5, 2016. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Upon our arrival in the village of Randelle, we decided the risk had been worth it. Beyond the houses destroyed by the floods, cholera threatened to kill those who hadn’t drowned. Reporting on the situation of these people was vital. Back on dry land a few hours later, I called local politicians to inform them of what was happening. They said there was nothing they could do.

Patients with cholera symptoms receive medical atention in a small clinic, in Randelle, Haiti, on October 19, 2016. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Patients with cholera symptoms receive medical atention in a small clinic, in Randelle, Haiti, on October 19, 2016. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

These days, I don’t tell foreigners not to asking why there is a crisis in Haiti, because there are so many questions to be asked.

Why do prosecutors and the courts refuse to investigate Haitian officials who can build themselves magnificent houses, while an ever-increasing number of people live below the poverty line?

Why does the Haitian revolution not have its place in history books alongside the French and the American ones?

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Why do some media outlets choose to call Haiti the “poorest country in the northern hemisphere” (debatable) rather than “the first black republic in history,” which is a more lasting and positive truth?

Why does the Haitian police violently suppress demonstrations that citizens organize to protest the fact that the country isn’t safe?

Why do certain supplies, such as firearms and ammunition, arrive in the country without any apparent difficulty, allowing gangs in a country where no guns are built to create havoc on the streets? Since the beginning of the year, armed gangs have tightened their grip in Haiti, and clashes between rivals have forced thousands of residents to flee certain poor areas of the capital.

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

Why do foreign prosecutors of financial crimes not worry about the crazy amounts siphoned from Haitian government accounts, which assuredly end up transiting, if not landing, in their banks?

Why did the country have wait until July to get its first coronavirus vaccines?

Why was the president killed in his bedroom, in what is probably the most heavily-guarded residence in the country, without anyone other than his wife ending up injured?

Yes, “Haiti is complicated.” And it’s important to keep asking questions – of Haiti’s leaders, at all levels.

Port-au-Prince, December 25, 2017. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

Port-au-Prince, December 25, 2017. (AFP / Hector Retamal)

These questions must also be put to certain long-serving diplomats in the capital, self-proclaimed experts in Haiti who do back-to-back tours in Port-au-Prince. They sometimes chuckle about how surreal life has become during the current crisis. They forget that the level of danger present in the streets of Port-au-Prince, which they avoid by traveling in bulletproof cars, allows them to benefit -- on top of their already generous salaries -- from hardship pay that alone is more than what a police officer earns, if he manages to get paid at all.

We have to ask questions because Haiti’s young people, who just want to live a normal decent life, deserve it. In the words of late Haitian singer and actor Toto Bissainthe, from an interview she gave in 1984: “The people suffer but we live. We celebrate, we fall, we pick ourselves up, we carry on, we starve but things are changing and they are always changing.”

(AFP / Hector Retamal)

(AFP / Hector Retamal)This blog was written by Amélie Baron, correspondent in Port-au-Prince. Translation: Eléonore Hughes in Paris