Broken-hearted in Beirut

“I never thought a day would come when survivors of the war would tell me there was something worse during peacetime,” writes Beirut’s deputy bureau chief Layal Abou Rahal. Born halfway through Lebanon’s devastating 15-year civil war, she never imagined the heart-ache, hunger and hopelessness her country would experience more than two decades later.

Beirut - I did not experience at first hand Lebanon’s civil war. I never had to run to an underground shelter to hide from the shelling and gunfire. I was born in 1983, when the conflict was still in full swing, but grew up in a remote village in southern Lebanon that miraculously escaped the fighting. I had a normal childhood.

(AFP / Joseph Eid)

(AFP / Joseph Eid)But over the years, I have heard the stories from my parents, my relatives, and the friends I made when I moved to Beirut, all scarred by the war from 1975 to 1990. I devoured books, articles and documentary films. I learnt from the testimonies of former fighters, who had decided to dedicate the rest of their lives to peace.

After a car bomb, Beirut, August 8, 1986 (AFP/ Khalil Dehaini)

After a car bomb, Beirut, August 8, 1986 (AFP/ Khalil Dehaini)My husband too was a child of the war generation. Elie was two years old when the conflict broke out, and 17 when it finished.

These days he watches on with an amused smile as I lose patience waiting in line at the pharmacy, the baker’s or the supermarket. He tells me how, when he was younger, he moved homes four times, and was two years behind in class because of the fighting. He spent nights in shelters, counting how many shells had fallen outside, and waited for hours in queues for water, a gas canister, or a single bag of bread.

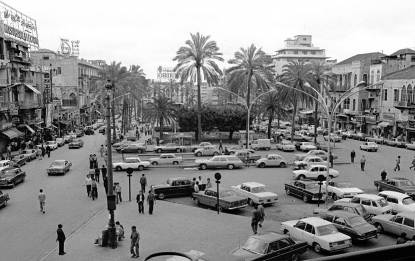

Beirut, November 15, 1976, one and a half year after the start of the war (AFP/ Xavier Baron)

Beirut, November 15, 1976, one and a half year after the start of the war (AFP/ Xavier Baron)As a journalist, I have covered many political crises in the multi-confessional country where I was born. More often than not, they are the consequences of a civil war that ended with a general amnesty law, but no real reconciliation.

Minarets of mosques surround the tower of a church at sunset in the Lebanese capital Beirut's downtown district on September 4, 2020. (AFP / Joseph Eid)

Minarets of mosques surround the tower of a church at sunset in the Lebanese capital Beirut's downtown district on September 4, 2020. (AFP / Joseph Eid)

Lebanon marked 46 years last week since the start of the conflict that killed 150,000 people and left 17,000 missing.

On April 13, 1975, clashes erupted in the Lebanese capital between Lebanese Christians and Palestinians backed by leftist and Muslim factions. Over the next 15 years, the war raged in Beirut. Frontlines cut people off from their neighbours, families and friends. Massacres repeatedly made headlines. At some checkpoints, people were abducted merely because of their religious identity. Hundreds of thousands of Lebanese fled seeking safety for their children, swelling the ranks of the Lebanese diaspora.

I never thought a day would come when survivors of that war would tell me there was something worse during peacetime. But the country’s economy collapsed in late 2019, and now they are scared, staring poverty and hunger in the face.

Tripoli, June 17th 2020 (AFP / Ibrahim Chalhoub)

Tripoli, June 17th 2020 (AFP / Ibrahim Chalhoub) Saïda, June 18th 2020 (AFP / Mahmoud Zayyat)

Saïda, June 18th 2020 (AFP / Mahmoud Zayyat)To die from shelling is better, at least there is no suffering... while today, we suffer and die slowly every day,” Abla Barotta, 58, told me a few days ago when I interviewed her for a story to mark the anniversary.

She had survived both the civil war and what she called “the corruption blast”, a massive explosion triggered by a fire in hundreds of tonnes of fertilizer stored at the Beirut port last summer that killed more than 200 people and ravaged large parts of the capital. Life was better during the war, says the widowed mother of three.

Abla Barotta, 58, has survived both the civil war what she calls “the corruption blast”,but she says life was better during the war (AFP/ Anwar Amro)

Abla Barotta, 58, has survived both the civil war what she calls “the corruption blast”,but she says life was better during the war (AFP/ Anwar Amro)“We used to hide in houses or basements every time we heard shelling during the war, but today, where can we go to hide from hunger, the economic crisis, the coronavirus pandemic and our political leaders?” she said.

Many among the older generation believe even the darkest days of war were kinder than the current “humiliation” of struggling to make ends meet.

Protest in Tripoli against the deteriorating living conditions (AFP/ Joseph Eid)

Protest in Tripoli against the deteriorating living conditions (AFP/ Joseph Eid)As the economic crisis has grown worse, my mother-in-law has repeatedly told us that she has never experienced such a “fear of the unknown”, never worried so much about what the following day would bring.

I recently visited her as she was recovering from a bout of the novel coronavirus. On television, an official was holding a press conference, but she was not interested in turning the volume up to listen. “Everything they’ve been saying for years is lies,” she said. Many no longer believe in the political class, or its ability to resolve the crisis.

A year and a half ago, unprecedented protests rocked Lebanon. Tens of thousands took to the streets in October 2019 to denounce deteriorating living conditions, and demand the complete overhaul of a political class they accused of incompetence and corruption.

October 20, 2020 (AFP / -)

October 20, 2020 (AFP / -)

But today protests have dwindled, even if the economic crisis has grown far worse. Many have emigrated, while others have lost hope or are too busy struggling to survive.

The value of the Lebanese pound has plummeted on the black market, prices have soared, and tens of thousands have lost their jobs or part of their salaries. Drastic capital controls have trapped people’s savings in the bank. Meanwhile, politicians seem to live on another planet. For eight months, they have been unable to form a new government.

Lastly there was the explosion in the port of Beirut on August 4, 2020. It killed 200 people, left 6,500 injured and devastated whole districts of the city. For Lebanese people already brought low, it was one tragedy too many. It will traumatise them forever.

Beyrouth, 6 août 2020 (AFP / Patrick Baz)

Beyrouth, 6 août 2020 (AFP / Patrick Baz)

An injured man sits next to a restaurant in the trendy partially destroyed Beirut neighbourhood of Mar Mikhael on August 5, 2020 (AFP / Patrick Baz)

An injured man sits next to a restaurant in the trendy partially destroyed Beirut neighbourhood of Mar Mikhael on August 5, 2020 (AFP / Patrick Baz)I did not experience war, but the endless queues outside bakeries, petrol stations and pharmacies today are very like the archive images of people lining up for bread broadcast in the run-up to the civil war anniversary. People’s lives have changed.

Poverty has risen to more than half of the population, the United Nations says. Middle-class Lebanese, once able to buy the latest car and travel abroad each year for holidays, are busy trying to prepare for more shortages or price hikes. Friends and family have dedicated a room in their flat to stock up on diapers, milk formula or detergent.

(AFP / Joseph Eid)

(AFP / Joseph Eid)In supermarkets, some imported products have disappeared from the shelves, or their prices have increased. Fights have erupted between customers over cheaper subsidized goods.

I used to enjoy grocery shopping, but today I am overcome with guilt that I can still afford to fill my cart. Nearby, a father persuades his son to buy a cheaper brand of coffee, or a woman puts a bottle of cooking oil back on the shelf after discovering it would cost around a fourth of the national minimum wage.

Maya Ibrahimshah, the founder and president of the Lebanese NGO Beit al-Braka (house of blessings) organises the stock of food to be distributed on February 23, 2021 (AFP / Joseph Eid)

Maya Ibrahimshah, the founder and president of the Lebanese NGO Beit al-Braka (house of blessings) organises the stock of food to be distributed on February 23, 2021 (AFP / Joseph Eid)A few weeks ago, I went shopping for myself and my parents who live outside Beirut. At the till, a woman in her forties was growing increasingly impatient with me. She wanted to pay for just a few items, while my trolley was almost full. “Some live in luxury and are not ashamed, while others are dying of hunger,” she suddenly said sharply, loudly. I was shocked. I felt a mixture of anger, embarrassment and sadness.

A Lebanese woman displays the content of her refrigerator at her apartment in the southern city of Sidon on June 16, 2020 (AFP / Mahmoud Zayyat)

A Lebanese woman displays the content of her refrigerator at her apartment in the southern city of Sidon on June 16, 2020 (AFP / Mahmoud Zayyat)I did not know if I should try to defend myself. I pushed my trolley out, and once outside removed my mask to breathe in deeply, trying not to cry. I grew up in a middle-class family, one of three siblings. My father retired in 2019 after 45 years of working as a teacher, but today after depreciation his pension is worth just 200 dollars.

My brother, a bank employee, is struggling to support his family. My sister a few years ago moved to Dubai with her husband. A few days after the incident in the supermarket, I saw a friend who works for an international NGO and who is paid in dollars. She told me how guilty she feels that receiving hard currency protects her from inflation and allows her to continue leading a comfortable life, while relatives are struggling.

As is the case in many families, she is trying to help them. But she wonders for how long she will be able to keep it up. “The situation is only getting worse,” she says.

Those who experienced Lebanon in the 1960s remember it as a golden era before the war and ensuing crises. On Facebook, an academic who is a friend recently explained that at least during the war, you knew one day it would end. But today “there’s no hope. The country as we knew it is finished,” he wrote.

Perhaps this loss of hope is what is most suffocating for our young people. Even those who are luckier than most say they have lost their “joie de vivre” -- this in a country famous for its love of partying, even throughout the country’s toughest periods.

Mask-clad pedestrians walk past a mural painting on September 4, 2020, depicting a young Lebanese girl who suffered a face injury in the August 4 massive blast (AFP / Joseph Eid)

Mask-clad pedestrians walk past a mural painting on September 4, 2020, depicting a young Lebanese girl who suffered a face injury in the August 4 massive blast (AFP / Joseph Eid)My friend Oumaima, a nurse in a prestigious Beirut hospital, told me a few weeks ago she was moving to Saudi Arabia. "I hate the idea of leaving, but I no longer have the strength to go on,” she said. “It’s not to get a better salary, but here is too draining.” Another friend, the mother of a little boy, said: “Our parents lived through a war of rockets and bullets, we’re experiencing a war of hunger.” “The most important thing is that our children don’t stay in this dump,” she said. She was describing a country which was once famously dubbed the Switzerland of the Middle East.

(AFP / Patrick Baz)

(AFP / Patrick Baz)Text by Layal Abou Rahal translated by Alice Hackman in Beirut. Edition: Michaëla Cancela-Kieffer in Paris