Unravelling a Havana mystery

Havana -- It caught my eye as soon as I walked into the Havana bureau -- an old Underwood typewriter, in mint condition, perched on a bookshelf at the entrance.

It wasn’t surprising to find such a relic. Cuba is a country where one often sees things from the past -- from vintage American cars from the 1950 to Russian motorcycles with sidecars from the 1970s or old retro signs -- because the island had been under a US embargo for decades, its residents have used many things that have long since been discarded elsewhere.

But I was intrigued. What stories could this machine tell, what secrets was it keeping? What scoops were tapped out on its round keys?

Soon after I began my posting as Havana bureau chief last September, we began to prepare a package of stories ahead of the 60th anniversary of the Cuban revolution, which is marked in the country in January.

With the untold story of the Underwood egging me on, I began to dig -- how did AFP cover those historic events in the first days of 1959, when revolutionary leader Fidel Castro declared victory after ousting US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista? Did our correspondents type their dispatches on this old typewriter adorning our office?

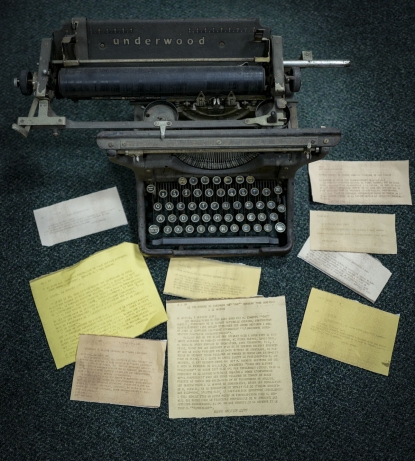

Dispatches around the Underwood used to write the first stories from Cuba following the Cuban revolution.

(AFP / Adalberto Roque)

Dispatches around the Underwood used to write the first stories from Cuba following the Cuban revolution.

(AFP / Adalberto Roque)I asked our archives department in Paris to send me all AFP production from that time. It all started with a one-line flash that AFP ran on January 1, 1959: “President Batista leaves the country.” I thought it would be easy to discover who wrote that historic flash and the first news stories of the Castro era. How wrong I was.

Today, all flashes, alerts and stories that AFP produces feature initials of the people who wrote and edited them. But back then, the stories weren’t signed -- there are no initials on the typed originals.

I knew that Jean Huteau would be key to unraveling this mystery. Huteau, who died in 2003, opened AFP’s first bureau in Havana in 1960 (he would later rise through the ranks to become “director of information,” the agency’s highest editorial post). But I wasn’t sure if he was already on the ground in 1959. So I began my search.

The first step started by reading all those old news articles.

Handout picture of Cuban leader Fidel Castro crossing a river on horseback in December 1958 in eastern Cuba, where he was stationed with his army.

(AFP / Ho)

Handout picture of Cuban leader Fidel Castro crossing a river on horseback in December 1958 in eastern Cuba, where he was stationed with his army.

(AFP / Ho)The style used back then was a bit different from today’s. Besides official statements, which we also cite today, the stories referred to “reliable sources” and “numerous rumors political and military in nature.” Some of the details were incredibly precise. A close aide to Batista, for example, “was apprehended when he was trying to enter a foreign embassy disguised as a priest.”

At times, the journalists seemed exasperated by the information flying around. “It is very difficult to verify all the noise,” one wrote.

Getting out of the office paid off back then as much as it does today. On January 8, a story stated that “An AFP correspondent entered Matanzas (a city east of Havana) with Fidel Castro’s troops,” which allowed him to get an “exclusive and impromptu” interview with Castro himself with his “bearded face that has now become a legend.”

I also got in touch with people who knew Huteau. On the Internet, I managed to find his daughter, Marianne, who today lives near Paris. When we talked, she warned me right away that her father never spoke to her at length about his work in Cuba. “He belonged to a generation that did not share much, and did not put oneself forward.”

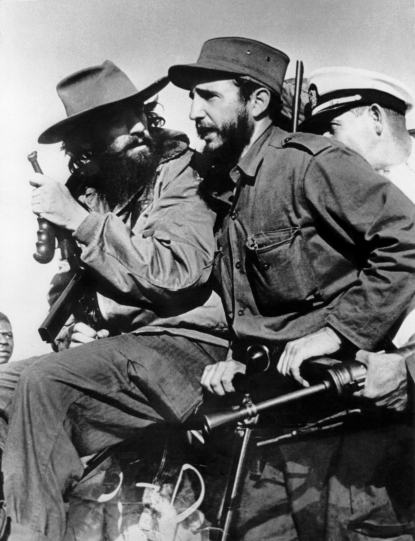

Fidel Castro (R) and another leader of the revolutionary movement, Camilo Cienfuegos (L), triumphantly enter Havana on January 8, 1959.

(AFP / -)

Fidel Castro (R) and another leader of the revolutionary movement, Camilo Cienfuegos (L), triumphantly enter Havana on January 8, 1959.

(AFP / -)She told me that he was studying medicine when the Second World War broke out and after the war left “to start a new life in Buenos Aires.”

There, he worked as a correspondent for several French newspapers, before AFP hired him as its Buenos Aires stringer in 1958.

“When Cuba became interesting, he was sent there to help with coverage. Before, there was not much to say,” Henri Pigeat, AFP’s chief executive officer from 1979 to 1986, told me.

He spent some time living and working in Cuba by himself, before sending for his wife and their three children to join him, Marianne told me. Even then, the country hardly made for a stable family life. There was a curfew in effect, schools were closed and their dog Toani, a cocker spaniel, ran away during the Bay of Pigs crisis. Marianne, a small girl at the time, remembers entire days spent at the beach, how food was scarce and her teenage brother wanting to join the revolution.

Eventually her mother managed to get permission to go live with the children in Miami, while her husband stayed behind to work. “My father was very proud to work for AFP because at the time, news stories weren’t signed and he thought that news shouldn’t be associated with a person.”

In my search for the AFP journalist who wrote the first articles in 1959, I reached out to all the former Havana bureau chiefs that I could think of. One, Jacques Thomet, who worked in the bureau from 1979 to 1981, wrote to me that Jean Huteau “told me that he used to type his articles on an old typewriter. It should still be in your bureau.”

Fidel Castro's tomb at the Santa Ifigenia Cemetery in Santiago de Cuba, during the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Cuban revolution, on January 1, 2019. (AFP / Yamil Lage)

Fidel Castro's tomb at the Santa Ifigenia Cemetery in Santiago de Cuba, during the celebration of the 60th anniversary of the Cuban revolution, on January 1, 2019. (AFP / Yamil Lage)But I still didn’t know if he was in Havana in 1959. Marianne, along with several former Havana bureau chiefs, thought so, but couldn’t find a trace of him going there in her father’s old passports.

In a book he co-wrote on AFP, Huteau wrote that at the time, Carlos Tellez, a former professor at a journalism school in Havana, served as a correspondent for both AFP and Reuters (AFP didn’t have an English-language service back then, so we weren’t direct competitors with Reuters that we are today).

But looking at those news articles, I noticed that they were signed sometimes by an “AFP correspondent” and sometimes by a “special envoy.” If Tellez was the correspondent at the time, who was the mysterious special envoy?

At one point, I decided to go through the bureau’s old files (my colleagues were by now referring to me as Sherlock Holmes). I moved chairs to open drawers that haven’t been opened for years, wiped away the dust… until one day I found a huge, yellowed folder, marked “letters received.”

As I thumbed through the letters, I almost forgot my aim in starting this hunt. Reading them I got lost in glimpses of another Cuba, another AFP.

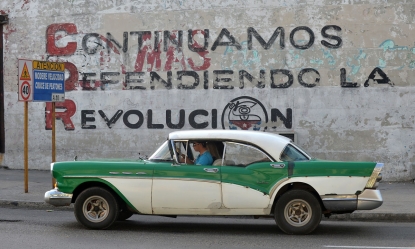

A car drives past a wall reading We Continue Defending Revolution referring to Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), in Havana on March 20, 2018. The CDR was created by Fidel Castro in 1960.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)

A car drives past a wall reading We Continue Defending Revolution referring to Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), in Havana on March 20, 2018. The CDR was created by Fidel Castro in 1960.

(AFP / Yamil Lage)For example, Huteau used to receive regular correspondence from an AFP department called “information control,” which scrupulously compared his coverage to that of the competition. “As a general rule, your work is good, complete and clear, “ said a March 1961 letter. “If the output is not always as good as its content would suggest, it seems to us that this is because of the delay in transmission between Havana and New York, which is rarely less than an hour and is often more than two hours.” Today our feedback usually comes by phone, from the global editor in chief’s office in Paris or the regional editor in chief.

More interestingly was a letter that I found from August 19, 1961: “Dear Sir, at your request… the Information Control department has carefully compared the originals of your stories to the texts that we have received.”

Apparently at the time, Huteau did not receive the actual AFP wire. So he couldn’t read the edited versions of his stories. But he suspected that his texts were modified when he sent them by telegram from Havana. The letter from Paris confirmed his suspicions: “We have uncovered numerous alterations, ranging from anodyne, to those of style but also including suppression of certain parts of the texts, or substitutions of tendentious passages.”

So the word “anti-Castronites” was changed to “mercenaries,” terminology used by the Cuban regime; the “communist” leader became a “leftist” leader and a reference to “food shortages” vanished altogether.

In an interview with Reporters without borders in 2003, Huteau was still fuming about the incident, not only angry with local Western Union employees who apparently made the modifications, but also with his AFP colleagues in Paris. “I was furious. And incredulous that my Paris colleagues could think for a second that I would write something like that.”

The new authorities in Cuba began to view the foreign press with suspicion as early as January 1959. Castro had invited 350 reporters from all over the world to cover the trials of Batista supporters. But he was quickly disappointed by the criticism from abroad of the expedited trials and ended up forbidding airing them on television or radio. Huteau was himself forbidden by the new authorities from leaving Havana without authorization.

A Sopka missile deployed during the missile crisis of 1962 is displayed at Morro Cabana complex, on October 11, 2012 in Havana. (AFP / Str)

A Sopka missile deployed during the missile crisis of 1962 is displayed at Morro Cabana complex, on October 11, 2012 in Havana. (AFP / Str)It was quite an experience reading all this. Today, our stories are carefully read by the Cuban foreign ministry, which does not hesitate to signal its displeasure, but they go directly to Paris and are not altered by pro-regime sympathizers at the local Western Union. But it’s still advisable to let the authorities know if we plan to travel outside the capital and any interview of a government employee -- from ministers to policemen or doctors -- require prior approval from the foreign ministry’s “international press center.”

Though it offered lots of interesting tidbits into the past, the yellowed folder did not answer my question as to who at AFP wrote those stories from the first months of the Castro regime. One of the letters confirmed that Huteau arrived in Havana for AFP in September. But who was there before him?

I had started to give up hope, when I suddenly received a message from Yves Gacon, who was once the director of the Latin America region.

“Following Castro’s victory, Jean Allary, who was at the time the head of the politics and diplomacy service at AFP, was sent to Cuba during the first quarter of 1959. We can say precisely the dates of his reportages, since he died in an airplane accident between Bogota and Lima in June 1959.”

At last, I had found the mystery reporter who had written those first dispatches of the new regime in Cuba. Jean Allary, who would be replaced by Huteau shortly after his death in the plane crash. My curiosity finally satisfied, I carefully put the yellowed folder away, all the while hoping that the Underwood would still be there in the bureau 60 years from now.

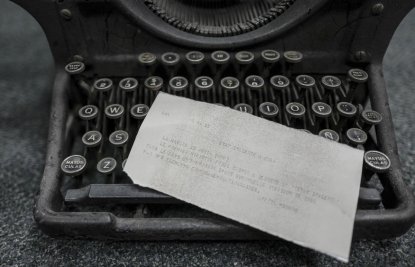

Picture of a dispatch and an Underwood typewriter used by AFP correspondent Jean Huteau in the first days of the Cuban Revolution, taken in Havana on December 25, 2018. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)

Picture of a dispatch and an Underwood typewriter used by AFP correspondent Jean Huteau in the first days of the Cuban Revolution, taken in Havana on December 25, 2018. (AFP / Adalberto Roque)