From Russia with... fun

Nizhny Novgorod, Russia -- Sergei my taxi driver was insistent on driving me somewhere I hadn't asked to go.

A bull of a man, well over 6ft tall and shaven-headed, he drove into what looked like the edge of a housing estate in Nizhny Novgorod, pulled over, got out of the car and asked for my phone.

It was my second day in Russia covering the World Cup.

The moon shines behind a lantern depicting a football next to the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium in Nizhny Novgorod, on June 26, 2018 during the Russia 2018 World Cup tournament. (AFP / Johannes Eisele)

The moon shines behind a lantern depicting a football next to the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium in Nizhny Novgorod, on June 26, 2018 during the Russia 2018 World Cup tournament. (AFP / Johannes Eisele)I had asked to go the city's brand new $290 million football stadium, where six tournament games were to be played.

But Sergei had other ideas.

Don't worry, he said, it will take just 10 minutes, whatever it was, as I tried to figure out where we were and if there was any escape route.

Both out of the car, he pointed me to a nearby small wall and then to the view -- the best in the city of the stadium. Then he found the camera on my phone and took pictures for me as a souvenir.

The stadium at Nizhny Novgorod, June, 2018.

(AFP / Johannes Eisele)

The stadium at Nizhny Novgorod, June, 2018.

(AFP / Johannes Eisele)For an encore, after finally visiting the stadium, he drove me back to the hotel, insisting on another stop, this time to buy me a local beer. The best local beer, he said, with a warm smile. My attempts to buy him one back were rebuffed, because, as he pointed out, he was driving.

In just a 30-minute drive round town, Sergei 's kindness and enthusiasm to show off his town -- and its beer -- squashed any unease I had about my month-long stay in Russia, shown me what to expect for the next few weeks, and unleashed self-disgust at thinking the worst even if for a few brief moments.

A view on the stadium in Nizhyny Novgorod, with the cathedral of Alexander Nevskyi in front. June, 2018.

(AFP / Johannes Eisele)

A view on the stadium in Nizhyny Novgorod, with the cathedral of Alexander Nevskyi in front. June, 2018.

(AFP / Johannes Eisele)Given the state of relations between Russia and much of the West, it was hardly surprising that people were worried prior to the World Cup -- and it is noticeable how fan numbers have been dominated by those from far away Latin America, instead of nearby Europe.

Covering a World Cup for a football nerd like me was meant to be exciting.

But prior to the tournament when I told people that I was heading to Russia, the reaction was less about how great it would be, but more how careful I should be.

The fact that I am British and relations between my home country and Moscow are so bad garnered even more concern.

Are you sure you want to go?, concerned people asked.

The Russian flag waving in front of the Kremlin in Moscow, July 1, 2018.

(AFP / Yuri Kadobnov)

The Russian flag waving in front of the Kremlin in Moscow, July 1, 2018.

(AFP / Yuri Kadobnov)Russians are fond of asking: "Otkooda?" Where are you from?

I was ready for this and had practiced.

So, when I first arrived, I answered confidently and obviously told anyone who asked: "Ya Irlandskii." (I'm Irish). No one could take offence at that, everyone loves the Irish, they are the opposite of my home country.

But within a few days, reassured by the friendly atmosphere, that had changed to "Ya Angliskii". (I'm English). I've kept saying it; in fact, I've never had so much fun saying it.

The welcome from Russians has been fantastic.

Happy locals in Moscow, July 1, 2018.

(AFP / Konstantin Chalabov)

Happy locals in Moscow, July 1, 2018.

(AFP / Konstantin Chalabov)From gentle amusement at foreigners' attempts to speak faltering Russian -- apparently when I ask for a bag at the nearby supermarket, my pronunciation of "sumka" is way too close to the Russian word for a female dog, which elicits fits of laughter from the bemused locals -- to being warned of the perils of a loose shoelace in a museum by a kindly and alert babooshka, to the efforts ensuring a colleague could get a taxi, locals in Nizhny could not have been more helpful.

And embracing Russia followed fear on our part; wide-eyed foreigners remarking on little things like the lack of litter, that trams stop in the middle of the street, passengers get off and no one gets run over, through to the joys of Georgian and Uzbek restaurants.

Similar stories have been relayed by colleagues all round this vast country, but the fact that I have got such a welcome in Nizhny is to me somehow more impactful.

The moon shines over the Nizhny Novgorod stadium situated behind the cathedral of Alexander Nevskiy in Nizhny Novgorod, June, 2018.

(AFP / Johannes Eisele)

The moon shines over the Nizhny Novgorod stadium situated behind the cathedral of Alexander Nevskiy in Nizhny Novgorod, June, 2018.

(AFP / Johannes Eisele)Nizhny Novgorod was once a town closed to foreigners during the Soviet era and every reporter here (including yours truly) has said or tweeted as much in the past few weeks.

But it is astonishing to think that as recently as 1991 -- barely history, more recent past -- the tens of thousands who have visited in the past few weeks would not have been allowed anywhere near the city.

Locals speak about how tourists used to take night time boat trips along the River Volga to where it meets the River Oka -- the Strelka -- one of the city's most famous natural landmarks, to catch a glimpse of the mysterious place.

Legend has it that until the 1970s there were no street maps of the city.

Every day in Nizhny is a day looking at that recent past. You can even visit its most famous former resident's house - the tiny apartment once home to Andrei Sakharov in the 1980s, a Soviet dissident and Nobel Peace prize winner, some 10 kilometres south of the city centre.

Inside the Sakharov museum in Nizhny Novgorod. (Photo courtesy of David Harding)

Inside the Sakharov museum in Nizhny Novgorod. (Photo courtesy of David Harding)His every move was watched, his apartment routinely searched to prevent the famous dissident from having any contact with foreigners.

Now a museum in an apartment block, today it stands opposite a McDonald's restaurant.

And if it is astonishing for foreigners, imagine what it is like for locals watching this cast of strangers descend on their city.

And what a mix it has been.

If there is a local who has never left Nizhny and made their observations only on those who have visited in the last two or three weeks, they would determine that all Swedes dress in yellow football shirts all day, regardless of whether there is even a match...

(AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

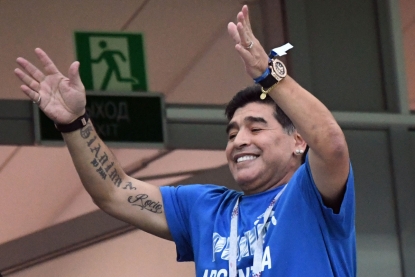

(AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)...Croatians go everywhere in groups, including breakfast; Argentinians are full of drama (this may be true)...

Argentina's football legend Diego Maradona gestures in the grandstand before the Russia 2018 World Cup Group D football match between Argentina and Croatia at the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium in Nizhny Novgorod on June 21, 2018. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

Argentina's football legend Diego Maradona gestures in the grandstand before the Russia 2018 World Cup Group D football match between Argentina and Croatia at the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium in Nizhny Novgorod on June 21, 2018. (AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)...and Panamanians are truly the happiest people on earth (this may also be true).

A Panama fan poses before the Russia 2018 World Cup Group G football match between England and Panama at the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium in Nizhny Novgorod on June 24, 2018. (AFP / Johannes Eisele)

A Panama fan poses before the Russia 2018 World Cup Group G football match between England and Panama at the Nizhny Novgorod Stadium in Nizhny Novgorod on June 24, 2018. (AFP / Johannes Eisele)Locals have told me that there are no issues with the influx of fans and tourists who have descended onto the city.

"I guess the people from another generation, they are not that open like us," said Kseniia, a 27-year-old who speaks at least three languages. "For them it's more complicated to communicate with people from abroad, but for us it’s very much easier."

Ivan, 35, says the major problem for locals is language rather than mixing. "It's a lot of time since the city was closed," he says, matter-of-factly.

Russians have noticed the difference .

One paper Vedomosti has remarked how lovely it is to see Russians smiling and happy, and wondered what will happen when the World Cup circus moves on after July 15.

Happy Russians. Nizhny Novgorod, June, 2018.

(AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)

Happy Russians. Nizhny Novgorod, June, 2018.

(AFP / Dimitar Dilkoff)For those of us here briefly, it has been a lovely, cosy bubble to live in.

A time when you wake up in the morning and think less about bad news around the world but instead what formation Switzerland/Senegal/South Korea might play that day.

And, yes, I am old enough to know that the feeling will not last, that the first controversy concerning the World Cup will come straight after we have all gone home - probably concerning data - and it will need more than VAR to make the host country and my home country friends again.

But for just a few weeks, it has been the one thing people predicted it would not be: fun.

Children play atop a Soviet T-34 tank at a local military museum in Nizhny Novgorod on May 21, 2018. (AFP / Mladen Antonov)

Children play atop a Soviet T-34 tank at a local military museum in Nizhny Novgorod on May 21, 2018. (AFP / Mladen Antonov)