A place no-one wants to be

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US -- Before I even found a place to park my car, I saw a man shooting up. Dressed in dark pants with his sweatshirt halfway off to expose his arm, he stood on the litter-strewn sidewalk, swaying as he fed the needle into his arm.

I had just pulled into the Kensington neighborhood of North Philadelphia to follow up on a story I had heard on the radio. Stretched along a half-mile of commercial rail tracks, there was said to be the largest open-air drug market in the eastern United States. The area had a significant heroin problem -- so much so that every six months or so one news outlet or another was breathlessly reporting on how terrible and unprecedented the addiction menace here was.

A man injects himself in the foot with heroin near a heroin encampmentin the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

A man injects himself in the foot with heroin near a heroin encampmentin the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)What I saw upon arrival certainly bore out the impressions from the reports I had read -- that the neighborhood surrounding the gulch had some of the worst poverty rates in the nation. The poverty rate of the Kensington area, along with a few similar zones, is why Philadelphia is ranked as America's most impoverished large city.

Technically, the tracks and adjacent embankments are the private property of a regional freight company, but as far as anyone visiting is concerned, it’s no-man’s land. Old sofas, television sets, car tires, and fast-food rubbish are deposited onto the slopes almost daily, with homeless individuals and drug users repurposing whatever is useful and taking shelter under the overpasses.

Freight cars rumble past a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Freight cars rumble past a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)I wasn’t particularly surprised by the urban blight and abandonment hanging over this once strong working class part of town. But when I ducked below the Second Street bridge, I entered a different world. There I was met with a cascade of household and commercial rubbish, papered over by a moss-like layer of paper syringe wrappers, the needles they once contained poking through here and there like shining silver thistles.

Household trash and empty needle wrapper paper is seen next to rail road tracks near a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Household trash and empty needle wrapper paper is seen next to rail road tracks near a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)Against this desolate landscape, groups of mostly men were hunched over improvised tables and chairs preparing and administering doses of intravenous drugs to themselves and one another. Some had the weathered look of many nights outside, while others had a fresher appearance of access to a bed and laundry. Some eyed me suspiciously as I passed closely by; others drifted catatonically in a standing semi-fetal position -– a real-life walking dead. My nostrils were assaulted by a fetid smell of burning plastic and human waste.

I later learned that the particular area where I came in was known as the “hospital” where, for a fee, users whose bodily veins had hardened too much could receive an injection in their neck or elsewhere. Many of the folks here were simply trying to get some relief from opioid withdrawal, known around here as being “dope sick.” You could easily spot a “dope sick” person because often he (most were men) were shaking and moaning in agony.

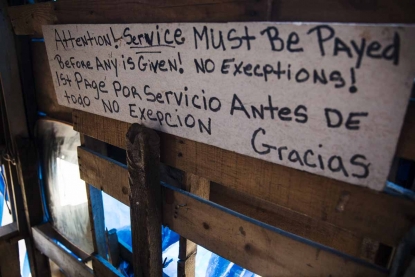

A bi-lingual sign describing terms of service is seen at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

A bi-lingual sign describing terms of service is seen at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)Some of the activity in the place noticeably slowed as I approached. The tension was palpable, so I made a wide circle to try to avoid confrontation. As I made my way along the tracks and below an embankment, a person called out to me. Grateful to have someone to speak with, I cautiously navigated a small path in the refuse up to a young man tending a fire in a barrel.

He asked if I was police, and told me that most of the folks around were suspicious of me. I had to admit I certainly looked a bit like a plainclothes officer (there’s still a uniform of sorts: boots, button-down shirt, baseball cap), especially since I was keeping my cameras concealed in my small black backpack until I had gotten a sense of the situation.

That’s how I often work on stories like these -- I rarely take out my camera on my first foray, but walk around, talk to people, get a feel of the place, tell them what I’m doing so they can get used to me, so I don’t intrude on their privacy and dignity. Only once there is a certain comfort level do I take out my camera and start shooting.

Steve, an addict, walks up to the street after getting high at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Steve, an addict, walks up to the street after getting high at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)And so I explained to the young man what I was there to do –- to truthfully document the situation and allow my audience to see something they otherwise wouldn’t know about -– and what I wasn’t there for –- to pry into people’s personal business or get them into legal trouble. Gradually others grew curious and stopped by and I’d repeat the explanation. People grew more tolerant of my presence, but no-one was yet comfortable being photographed, so I just hung out and asked as many questions as they would accept until they asked me to go elsewhere to give them some space. Gradually I started to see the rhythm and the rules of the place and was starting to get a sense of how it functioned.

Then two men who had come down from the overpass started to chat with me. One of them was particularly interested and understanding of what I was doing, but told me bluntly “we came down here to buy heroin, but nobody is selling because of you.” Seeing the startled look on my face, he followed up, “people are starting to get [dope] sick, because they won’t sell while you’re here.”

A man injects a shot of heroin near a heroin encampmentin the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

A man injects a shot of heroin near a heroin encampmentin the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)I thanked him and turned straight around and started walking conspicuously down the middle of the railroad tracks, away from the overpass, hoping I hadn’t caused too many people too much harm. On my walk I explored the other bridges and gulch embankments where it seemed half of Philadelphia had taken to dumping everything they didn’t know what to do with. Household furniture, auto parts, children’s toys, all flowing in ultra slow motion from the streets above down toward the tracks.

As I approached a final bridge, I heard the hiss of someone trying to get my attention. Up by the fencing I saw a man crouched in hiding waving at me, then gesturing ahead down the tracks, where I saw a Philadelphia police cruiser rolling slowly toward me.

If a few moments before my problem was drug dealers and users thinking I was a cop, now I was at risk of cops thinking I was a user or a dealer. I scrambled up the embankment out of sight and hastily started to unpack my cameras and press credentials, next to a few needles and a pile of human excrement.

Philadelphia Police officers patrol under a bridge near a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Philadelphia Police officers patrol under a bridge near a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)Concerned that the police car would make it all the way up to the Second Street bridge, (suspiciously after I had left, no less) I circled around to the street and made my way back to the camp to tell the first man I had met that while I was not a cop, there were cops in the area. I lingered a while a longer near the camp and spoke with folks as they were willing.

Soon enough, people again began telling me I shouldn’t be there, couldn’t stand where I was, needed to leave, etc. All things a photojournalist is pretty used to hearing on a regular basis. Given that all of us were trespassing on corporate property, I knew I had as much legal right (ie none) to be there as anyone else and stayed put. Eventually one man kindly took me aside and explained, “they’re asking you nicely now – soon they won’t be so nice.” He went on to say again that business was grinding to a halt on the rumor of a cop (me) in the camp, and that people were again getting dope sick.

I thanked him for his candor and advice and asked if he would walk with me and explain a bit more about the encampment and how he ended up there. He told me he was a functioning addict, who managed to retain a regular full-time job and own several houses. He only started using heroin after being prescribed pain-killers and having his insurance lapse on the opiates. At $7 a bag, heroin was a bit cheaper than black-market pills and vastly cheaper than brands like Percocets or Ocycontin.

A stuffed toy hangs from a tree near a table and mirror at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

A stuffed toy hangs from a tree near a table and mirror at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)He told me he would come down to the camp once or twice a week, usually with a great deal of cash, to get “the work” as well as pay for doses for those who were succumbing to withdrawal but couldn’t afford a hit. He also said he would spring for packs of clean needles, sourced from the nearby needle exchange program, Prevention Point. The needles from the exchange themselves are free, but someone has to do the work of gathering up the used needles and making the trade.

As with anything of value here, clean needles have quickly become a feature of the micro economy, with a 10-pack of clean needles worth a small bag of extraordinarily pure Mexican heroin. So whether it’s a functioning addict paying cash, or a homeless or penniless user trading dirty needles for clean ones, it’s shockingly easy to come up with enough for a bag of dope.

Discarded needles are seen at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 7, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Discarded needles are seen at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 7, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)I left after the first day empty-handed as far as pictures since nobody yet felt comfortable with my camera, but I tried to leave on good enough terms to return. I heard that a television crew would film a special in the camp the following Monday, so I decided to return then, to fly under the radar of their disruption and get some of the environmental pictures I had avoided when the camp was busy.

When I came back, I met a woman who had taken time to talk with me on my first visit, and who hadn’t been scared off by the production crew and inter-agency police presence. We chatted for a bit and she agreed to let me follow her around and meet some of the other locals on a later visit.

Jessica, a homeless heroin addict, describes how she tested positive for HIV after being raped last year in this spot under the bridge where she lives in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Jessica, a homeless heroin addict, describes how she tested positive for HIV after being raped last year in this spot under the bridge where she lives in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 14, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)Now with a personal contact vouching for the fact that I was who I said I was, and doing what I said I was doing, I would be able to get some of the more immediate images of people using. Most were reluctant to have their faces included when they were using, and anyone who didn’t verbally agree to be pictured we left alone entirely.

In the course of my reporting, I would hear about professionals in suits and medical scrubs stopping into the gulch for a daytime fix, and meet others who seemed to live fairly typical lives. I’d also meet and get to know folks who had such typical lives fall to pieces at the end of the needle and were desperate for a change.

Steve, an addict, pauses for a moment after getting high at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Steve, an addict, pauses for a moment after getting high at a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)Time and again they told me their stories of how they had lost family, homes, and years of their lives to heroin – often as they were busy mixing up a dose. After allowing me to watch them inject, they’d continue telling me about their situation as they conscientiously snapped the tip off the used needle to prevent re-use or an accidental prick, before throwing it onto the growing garbage heap. (City workers I talked to told me that those who do cleanups in the area receive regular screenings for HIV and similar infections.)

This was a tough assignment for me. On the one hand, it was an important story and the type of work that I’ve spent my career preparing for. I had worked on tough stories before, but usually in coordination with a writer who would make the first contacts or at least be a second pair of eyes and ears on the scene. On this one I was completely on my own, with some pretty delicate logistics to manage.

But at no point in the three days that I visited the camp did I ever want to be there. The combination of the raw human pain on display, the desolate environment, and the mental challenge of keeping my head on a swivel against risks while making thoughtful pictures was a lot to balance. Although that feeling lingered throughout the story, it was fairly shoved into the background within the first half hour on my first day when I could see that no-one wanted to be there. For nearly everyone I met, there was simply nowhere else to go.

A graffiti portrait looks out from behind a mattress in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

A graffiti portrait looks out from behind a mattress in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)My hope in making the photographs and in reporting this story was to make the issue real to people in a way that gets easily lost in statistical reports, newspaper headlines, op-ed pieces, or political speeches. If anything illustrates the magnitude of the addiction crisis in this country, it is Kensington. And if anything is going to work in response, it will have to pass the test in North Philadelphia.

Household trash and empty needle wrapper paper is seen next to rail road tracks near a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)

Household trash and empty needle wrapper paper is seen next to rail road tracks near a heroin encampment in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on April 10, 2017.

(AFP / Dominick Reuter)