The devil hides in your email attachments

Paris, April 19, 2016 -- I am always amazed by what I discover working in the IT world, especially within its darker regions.

In just a few years, we've moved from crude cyberattacks that did some damage, to intense malware campaigns whose severity, scope, and sophistication I still have trouble wrapping my head around. One instance I'll never forget happened when I came to work on the morning of March 1.

(AFP / FRED TANNEAU)

(AFP / FRED TANNEAU)I'm the chief information security officer for AFP. My job, among other things, consists of trying to stop rogue attacks and hackers from infiltrating our computer systems. To make this job a little easier, in addition to our automatic security sweeps, I regularly ask AFP employees all over the world to send me emails they believe could be harmful. It's by analysing these messages that I'm able to sound the alarm immediately if something happens.

This is my morning ritual when I hop on the train to headquarters: I look at my inbox on my cellphone, trying to figure out what my day will look like. There are days with activity and days with nothing.

When I stared at my phone on that Tuesday, March 1, I could tell the day would be calm. I saw only a few causes for concern, but nothing major. Appearances, obviously, can be deceptive.

I had barely made it into the office before a colleague flagged me. "Come and see, I think I received a suspicious email." He sent me the email, and at almost exactly same time, my inbox was flooded with other messages telling me they'd received the same suspicious attachment. At first, it looked like it came from a respected law office in Paris.

The dreaded email.

The dreaded email.I immediately set out to do a quick systems search using some of our specialised IT software. Within a half hour, I found that the infected email had been sent to more than 2,000 AFP addresses worldwide. A piece of particularly nasty malware was embedded in the attachment which, at the time, our anti-virus software could not detect.

Within minutes, AFP's information systems office went into all-hands-on-deck mode. The security incidents manager and the operations team went to work to push back against the threat. I learned from calling the law office implicated in the email -- yes, it was a real office -- that AFP was not the only company hit with the malware. It looked like a massive attack.

Hackers had stolen the law office's email account and were using it to send out the virus. They apparently believed they could reach a maximum number of users that way, expecting us to fall into their trap by clicking on the malicious attachment.

(AFP / JOHANNES EISELE)

(AFP / JOHANNES EISELE)The first thing we did was block the law office's email address so it could no longer communicate with AFP's servers. At that point, however, it was already too late: 2,000 emails had got through. And unless a miracle had happened, it was inevitable that some users had tried to open the attachment.

So, what happened if you clicked on it?

At first, nothing. At least, nothing you'd be able to see. The attachment would seem empty, even if you clicked on it four or five times in a row. For many minutes, your computer would continue to function normally. You wouldn't have a clue that a terrible process had begun. In fact, the program you had just installed by clicking on the attachment was about to ruin your work day, and maybe even your life.

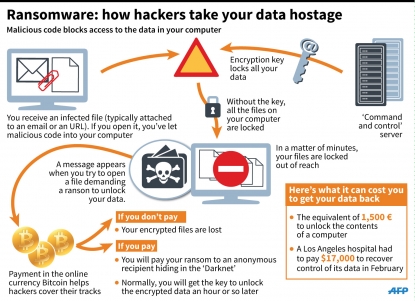

The malware turned out to be the powerful ransomware, Locky. Ransomware is a type of malware that, when activated, installs an extra bit of code on your hard drive. The code communicates with a server known as "command and control" located somewhere on the Internet, which then installs the rest of the virus and affixes a unique data encryption key to it.

The malware then takes over everything connected to the computer: it encrypts your computer's internal and external hard drives, any USB keys connected to the drives at that moment, and any other shareable content connected through your network. Everything becomes unreadable, unusable. All your computer's data is lost.

(AFP / PAUL J. RICHARDS)

(AFP / PAUL J. RICHARDS)After the computer is encrypted, a box would then pop up with a message from the hackers. Once you'd opened the message and read it, you'd realise how much worse the situation had become.

A few minutes after we discovered the attack, I got a call from a regional AFP bureau in France that a terminal had been compromised. I asked the IT engineer there to send me the email the person had clicked on. Bingo: it was the so-called law office's message we had all received. Little by little, we started to discover that computers were infected inside the Paris headquarters, and then some bureaus in Europe. We also found out that some file sharing systems over the server had likewise been encrypted.

At that point, I knew that things were bad, that the damage would be significant. We alerted AFP's chief information officer and the agency's CEO. The only bright spot was that, in the meantime, our anti-virus software had been updated with the malware's characteristics, probably because another company had fallen victim to the same vicious code in the past.

But the attack was barely getting started. The hackers' message that had been plastered on every infected computer announced that all data had been encrypted and would remain that way until a ransom was paid. It informed us of the procedure to follow to buy the data encryption key -- the only way to unlock the data being held hostage.

(AFP / FRED TANNEAU)

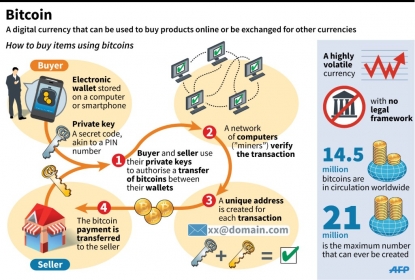

(AFP / FRED TANNEAU)To pay the ransom, we had to buy bitcoins, the independent, digital currency that, like cash, is virtually untraceable. For that attack, the ransom was fixed at four bitcoins per encryption key. The bitcoin, which fluctuates wildly, cost around 390 euros at the time. At that rate, it would cost us at least 1,500 euros to unlock the data of just one computer.

It was then that I understood how profitable this business could be for hackers. That day, they probably launched a campaign that saw their message go out to hundreds of thousands of email addresses. Even if only a thousand victims paid the 1,500-euro ransom, the math speaks for itself. March 1 would turn out to be a very good day for that group of hackers, thanks to your troubles.

(AFP / Graphics)

(AFP / Graphics)At AFP, we ended up with a fair number of infected terminals. In all cases, it was an understandable human error. An attachment from a respected law office in Paris wouldn't raise the suspicion of many of our users.

But we decided not to give into the hackers' demands. We alerted the police and isolated our infected computers. We reformatted them and restored the data throughout the day, but kept the encrypted files for the investigators. Perhaps they would be able to stop the hackers and find the server where they had hidden the encryption keys.

But what if we'd had no choice but to pay the ransom? In that case, we would have had to buy bitcoins. The next step would be to go on TOR, a browsing software application that allows you to communicate anonymously over the Internet, get the money to the hackers via some sort of bank account on the Darknet -- a hidden network often used for illicit ends -- and hope for the best.

(AFP / Graphics)

(AFP / Graphics)In general, within an hour of making the payment, the victim would receive a link to a server on the TOR network containing a "decryptor" -- a tool that would allow them to unlock their computer. These computers, protected by encryption keys called "2048-bit RSA," are nearly impossible to crack without a decryptor. This algorithm allows infinite possible password combinations that it would take a normal computer hundreds of years to crack -- even working 24 hours a day.

These attacks are so well organised that it's hard not to be somewhat impressed by their scope. Of course, we have no idea who the hackers are and how they did it. But we can see that these assaults take months to plan. For all we know, they could be a mafia-like organization structured like a corporate business, with computer programmers highly specialised in cryptology, computer scientists, translators who would be able send messages in various languages, accountants who deal with the bitcoin transactions, and so on. Maybe these people don't even live in the same country, having connected through the Darknet. They've probably never met in person, preferring to handle everything through virtual channels.

The Interpol cyber fusion center in Singapore in April, 2015. (AFP / ROSLAN RAHMAN)

The Interpol cyber fusion center in Singapore in April, 2015. (AFP / ROSLAN RAHMAN)Intelligence, or what we call social engineering, plays a prime role in choosing the victims, finding out their habits, and collecting their email addresses. Hackers probably rent servers in several places around the world and install the data encryption system there. Hackers generally base their servers in Russia or China, or in any country where a Western police force wouldn't be able to intervene easily. If the hackers were based in western Europe, for example, they'd be easier to catch.

Hackers also never send the same email attachment for each assault or the operation would be immediately discovered and instantly neutralised by anti-virus software. In today's world, it's literally a race between the hackers and the rest of the IT world; but hackers usually have a few hours' head start, time that the anti-virus software companies need so that they can get their software up-to-date and stop the threat. But it's usually enough time for hackers to make off with a few million.

An employee at a cyber security center in western France, February, 2016. (AFP / FRED TANNEAU)

An employee at a cyber security center in western France, February, 2016. (AFP / FRED TANNEAU)We later found out that their degree of sophistication knows no bounds. Very quickly after the beginning of the attack, we had been able to block the law office's email address so that AFP's servers stopped accepting the infected message. The next morning, a journalist emailed me saying she was surprised to have received a message from AFP's servers telling her a message she had supposedly sent to the law office had been rejected as undeliverable. But, she said, she had never sent such a message.

We knew then that the hackers had found a way around our security wall in order to send a delivery receipt confirmation whenever the law office's email was manipulated, transferred, or destroyed. The hackers devised it so they could confirm that an email account was real, that it belonged to a live person. This was unbelievably clever: at the same time as they were attacking, they were updating their email data for possible future attacks on the same people.

(AFP / ROSLAN RAHMAN)

(AFP / ROSLAN RAHMAN)When we're faced with such an assault, the priority is to contain it. Each attack has its unique modus operandi so reaction time is different. In Locky's case on March 1st, we were able to stop the attack within about an hour by blocking the email sender, clearing attachments, installing the updated anti-virus software on all computers, and by telling everyone working for AFP to stop clicking on questionable email attachments.

We regularly do computer security audits, testing for intrusions from outside sources. Today, all businesses have "firewalls" to protect themselves; they have an entire information system infrastructure in place to guard against attacks. My job also involves monitoring technology, working with my technical teams whose talents I highly value, and keeping an eye on all the alerts we get from the authorities. I regularly meet with key figures in the computer security field, such as anti-virus software publishers and editors. I also take advantage of the knowledge I gain from my peers in other French companies, experts in the computer security field.

A Black Hat logo at a cyber security conference in Las Vegas in August, 2015. (AFP / GLENN CHAPMAN)

A Black Hat logo at a cyber security conference in Las Vegas in August, 2015. (AFP / GLENN CHAPMAN)But all of this means nothing if people aren't vigilant themselves, if they aren't educated and connected. Today, hackers depend on users' gullibility and inattention. The less gullible and distracted users are, the less chance hackers will have to strike. Therefore, allow me to give you some advice:

- Beware of all email attachments and links in email messages. They're the perfect bait for a "phishing" attack, in which malicious software installed on your computer could ruin your life (it could be ransomware, but also spyware that would gather information on you and steal your credit card numbers). If you don't recognise the email sender, do not open the attachment. But even if you do recognise the sender, be alert: the email account could have been hacked. If you're not awaiting an email from them, it's better to contact them in person to make sure it's really from them. For links, the same practice applies. Start by hovering over it without clicking on it to see what the url says. If it's a well-known domain, something like afp.com, no problem. But if it's something like afp1.com, then you know it's a trap.

- If you receive a suspicious email, let the right people know. Forward it to your IT systems security team so they can analyse it and take necessary precautions. Hackers send personalised emails to each person to bypass company security screenings. If that person doesn't alert anyone, the threat stays undetected. Staying vigilant is absolutely critical.

A computer terminal at the US Department of Homeland Security, July, 2015. (AFP / PAUL J. RICHARDS)

A computer terminal at the US Department of Homeland Security, July, 2015. (AFP / PAUL J. RICHARDS)- If you do happen to click on the attachment or on the link, the best thing is to immediately turn off the computer by clicking on the power button or, better yet, unplugging the desktop from the wall. Ransomware takes at least several dozen minutes to kick into high gear to deploy its nasty process and encrypt files. If we shut off the infected computer, the process can't finish.

- Don't keep all your egges in one basket. Regularly make copies of all your important files on external systems, such as portable hard drives or USB keys that won't always need to be connected to your computer or the Internet. Or copy your files to a company server that makes frequent saves. You'll easily be able to recover any file you need if your computer is hacked, stolen, or breaks.

An employee at a cyber security operations center near the French city of Rennes, February, 2014. (AFP / THOMAS BREGARDIS)

An employee at a cyber security operations center near the French city of Rennes, February, 2014. (AFP / THOMAS BREGARDIS)One of the worst nightmares of an IT security supervisor happened to TV5 Monde in April 2015, a full-frontal attack that cost the French television station millions of euros. Hackers infiltrated the station's computer systems without detection and spent weeks, if not months, spying within the network. They were able to uncover the administrators’ account passwords. They took everything apart as soon as they pounced. A company can be brought to its knees like that, and take months to pull itself back together.

As for ransomware attacks, they've been around for a long time but organised assaults are a recent phenomenon. The first ones I saw occurred last year. Security experts say 2016 will be the year of ransomware. But let's not forget that numerous other types of malware exist and new ones appear every day. We have to learn to stay humble because airtight security simply does not exist.

(AFP / FRED TANNEAU)

(AFP / FRED TANNEAU)For someone who doesn't have his nose in every crazy plot in the world of information technology, it's hard to fathom just how dangerous that world is. In a company like AFP, we talk about every day attacks, those that could infect just a few dozen email accounts to millions.

When I was putting the finishing touches on this article, another message infected with the ransomware Locky was sent to about 400 AFP email accounts in a 30-minute period. Luckily, our anti-virus software had detected the attack and blocked it.

Of course, AFP journalists would much rather do without all the security constraints I put on them so they could send articles, pictures and videos without first having to enter all the various passwords they're required to have. I sometimes have to struggle with, and ultimately put aside, my paranoia, so as not to bother the journalists as they go about their jobs. But there are some moments where I have no choice but to be uncompromising, or we'd run the risk of a catastrophe.