COP21: Less than meets the eye

In a feverish dream last week, I found myself pouring over the final draft of the Paris Agreement moments after the UN presented it for approval to ministers from 195 nations. I frantically looked through the jargon-laden, 32-page climate pact for the silver bullet that would ensure victory in the fight against global warming. Just when I thought I might have found it, I woke up with a jolt.

And so it is, I suspect, for many journalists, analysts, activists and even negotiators embedded in the climate change saga. Six years – more than 20 if one starts the clock with the Rio Earth Summit – of maddeningly Byzantine negotiations, moving sideways or in circles as often as forward, have finally yielded a universal climate accord. But what, many of us are left wondering, has truly been achieved?

A lot.

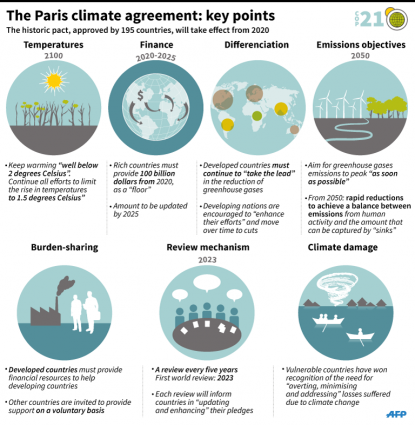

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)'Historic' 'landmark' accord

Headlines summing up the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) include the words “historic” or “landmark”. And the 3,000-plus journalists accredited to the 13-day marathon in suburban Paris have by now highlighted the Agreement’s key elements:

•For the first time, nearly every nation on the planet – from oil exporters to post-industrial economies to rapidly emerging giants to countries mired in poverty – has committed to curbing its heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions. Even North Korea signed on, vowing to “declare war” on deforestation.

•Having already decided in 2010 to cap global warming at two degrees Celsius above pre-Industrial Revolution levels, the newly harmonious family of nations opted in Paris for even greater ambition: “well below two degrees”, with a promise to "pursue efforts" to limit the rise in temperature to 1.5C.

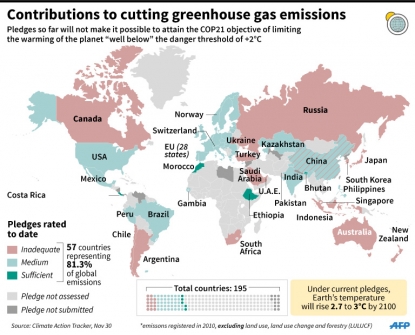

•Because voluntary, carbon-cutting commitments – when tallied – fall far short of the new target (or the old one, for that matter), nations have also agreed to revisit their pledges every five years. The hope is that new technologies backed by money will give countries the confidence and the incentive to speed up the transition from dirty to clean energy.

•To help ensure that promises are kept, the Paris Agreement lays out rules and procedures for verifying each country’s efforts. While there are no penalties for non-compliance, the system provides a common yardstick for progress and applies ‘name-&-shame’ pressure for adherence.

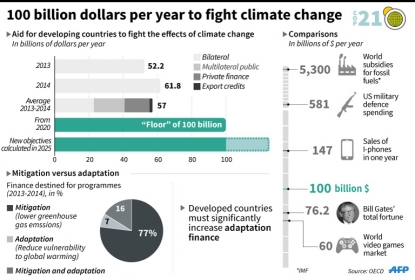

•The new deal details for the first time a pledge – made at the chaotic 2009 Copenhagen climate summit – to mobilize $100 billion per year for developing countries from 2020. The hard numbers have been relegated to a legally non-binding preamble so the Obama administration can end-run Republicans in Congress. But poor countries can now reasonably expect that amount to increase over time, and that roughly half the money will go towards helping them to prepare for climate impacts already in the pipeline – both hard-won concessions.

A coal power plant in Germany. October, 2015. (AFP / Patrik Stollarz)

A coal power plant in Germany. October, 2015. (AFP / Patrik Stollarz)Taking credit

Victory has 100 fathers, and defeat is an orphan, John F. Kennedy once said. The United States, France and China have each taken credit for the glorious outcome of COP21, as did green campaigner Bill McKibben on behalf of millions of grassroots activists around the globe. India could likewise lay claim to the laurel simply for not blocking the deal despite its deep misgivings.

A share of the credit should also go to the large cadre of legitimate policy experts (as opposed to fossil fuel lobbyists in sheep’s clothing) working at various points along a spectrum of advocacy ranging from business-backed think tanks to hard-core green groups and champions of the poor. Their knowledge and insights have been essential for all journalists covering this story.

In the tense hiatus between the release of the final draft and the 195-nation plenary that would either embalm or embrace it, journalists scrambled to collect reactions. We still did not know if Paris would be a success or a failure. During this Twilight Zone moment, which lasted a couple hours, I had one of two encounters that helped to shape my perception of this extraordinary event.

Delegates read copies of the COP21 agreement. December 12, 2015. (AFP / Miguel Medina)

Delegates read copies of the COP21 agreement. December 12, 2015. (AFP / Miguel Medina)As 20-odd AFP journalists worked the phones in our cramped, coffee-stained cubby hole, in walked Alden Meyer of the Washington-based Union of Concerned Scientists. Alden has been to every annual UN climate meeting since the inaugural COP in 1995, as well as most of the mind-numbingly technical meetings in between. He’s our top ‘go to’ guy when we need a quick answer or an insightful analysis, and I have spoken to him countless times over the last eight years.

As soon as I saw his face I somehow knew that the Paris Agreement was going to be adopted. He didn’t say that, of course. His words, as always, were measured. “It’s looking good,” he said. We peppered him with questions about which countries might object to which provisions in the text.

But what gave it away was his radiant expression, a mix of excitement, satisfaction and relief that I had never seen in him before. I imagined Sisyphus – condemned to push that cursed rock up the hill only to watch it tumble down again – suddenly realizing that he had finally tipped it over to the other side. Having watched Alden strain to remain upbeat through nearly a decade of impasse and setbacks, and knowing what it would take to satisfy him, to suddenly see him genuinely happy made me think, ‘maybe there is good reason to cheer’.

French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius (C) raises hands with UN chief Ban Ki-moon (second from left), and Franc'e President Francois Hollande after the adoption of the agreement. (AFP / Francois Guillot)

French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius (C) raises hands with UN chief Ban Ki-moon (second from left), and Franc'e President Francois Hollande after the adoption of the agreement. (AFP / Francois Guillot)You can’t, of course, go to the bank – or write a lede - with a hunch. But just then my colleague Mariette Le Roux rushed in. “I’ve got the LMDC on the record saying they’re on board!,” she blurted out. (Translation: The Like-Minded Developing Countries group – one of several formal negotiating blocs under the UNFCCC umbrella – houses virtually all the countries that might have torpedoed the Agreement, including India, China and Saudi Arabia.)

“Well then, it’s a done deal,” said Alden without missing a beat, before turning on his heels and walking out of our mini-newsroom so that Mariette could ‘storify’ her scoop.

Click here to watch on mobile device

Diplomatic and political coup

The title of this meandering reflection suggests another shoe is about to drop, and drop it will. But let it first be said that the Paris Agreement was a diplomatic and political coup.

For one thing, in the words of US Secretary of State John Kerry, it “restored the global community’s faith that we can accomplish things multilaterally.” That confidence had been nearly shattered by the debacle in Copenhagen, something UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon implicitly acknowledged last weekend when he said how disheartening that experience had been for him.

More fundamentally, it keeps alive the hope that humanity CAN rise to the challenge of replacing, in a few short decades, the very engine that powers civilization.

But what happened in Le Bourget is only a first step, a collective Letter of Intent. Now comes the hard part, one measured in numbers: gigatonnes of greenhouse gas, degrees Celsius, deadlines, ocean pH, parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. For unless we find a way to stay within our carbon budget – the rapidly dwindling lump-sum of CO2 we can put into the atmosphere without overshooting the 2C target (much less 1.5C) – then the Paris Agreement will ultimately be remembered as the deal that came 20 years too late.

Houseboats are moored on a shrinking arm of a California lake. May, 2015. (AFP / Mark Ralston)

Houseboats are moored on a shrinking arm of a California lake. May, 2015. (AFP / Mark Ralston)For months, France has seized every opportunity to contrast its handling of COP21 with the ill-fated 2009 summit in the Danish capital. Even in triumph, after French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius hammered through the deal to tears and cheers, he and French President Francois Hollande continued to rub salt into Copenhagen’s wounded pride.

That was not only oddly undiplomatic, it was unfair. Yes, Copenhagen fell horribly short of expectations, and ended with some 115 world leaders – to this day no one knows the exact number – scrambling to salvage their dignity and a deal. But it did yield the two cornerstones upon which the Paris Agreement was built: the 2C target and the $100 billion promissory note.

Perhaps the most significant difference between 2009 and 2015 is today’s global realization – what the French call a ‘prise de conscience’ – that climate change is a clear and present danger that will get much, much worse very quickly unless we do everything right. Even then, we’re counting on Nature to restrain its all-too-obvious capacity to overwhelm our puny efforts. In the end, that may have been the main driver of the Paris agreement: a sense of gathering fear.

A boat in a dried-up reservoir in Spain. August, 2006. (AFP / Pedro Armestre)

A boat in a dried-up reservoir in Spain. August, 2006. (AFP / Pedro Armestre)Too soon to declare victory

In any case, as many have said, it is far too soon to declare victory.

To start with, even if powerful vested interests have executed a tactical retreat, they have yet to play their final hand. Do we really expect oil exporting nations, a fossil fuel industry worth five trillions dollars, and the legion of politicians at their beck-and-call to go quietly into the night? “The climate bandwagon is rolling and gathering speed such that the fossil fuel industry will spend the coming years and decades in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons,” Brian Ricketts, Secretary-General of the European Association for Coal and Lignite, wrote recently to his members. “This is not a sustainable position and the industry should no longer acquiesce.” Fighting words.

Oil-smeared fingerprints are all over the Agreement itself, though the evidence is more what’s missing than what’s there.

Exhibit A: Burning fossil fuels is far-and-away the main cause of global warming. Period. To even have a chance of avoiding catastrophic impacts, upward of 80% of known oil, gas and coal reserves must stay in the ground. And yet, not once does the phrase “fossil fuel” appear in the 32-page text. The same goes for “carbon dioxide” and “CO2”. Talk about the elephant in the room! Nor is there any suggestion for creating a carbon tax, or removing $500 billion a year in fossil fuel subsidies.

A coal power plant in Germany. October, 2014. (AFP / Patrik Stollarz)

A coal power plant in Germany. October, 2014. (AFP / Patrik Stollarz)Here are a couple of (no doubt foolhardy) predictions:

•Before long, the term “overshoot” will enter the general climate vocabulary as scientists and then diplomats articulate the fact that we cannot get there from here without first racing past our target destination of 1.5C, and even 2.0C. Most climate scientists, if you look them in the eye, will tell you now that staying below the 1.5C cap is a pipedream.

•Yesterday’s climate skeptics will become tomorrow’s enthusiasts for re-tooling Earth’s climate system through technology, an approach often called geo-engineering. Whether it be injecting billions of tons of sulphate particles into the atmosphere to shade the Sun, or building machines to suck CO2 straight out of the air, they will acknowledge the problem but say it’s too late – and unnecessary – to radically draw down greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. We can keep our sooty cake and eat it too, they will suggest.

But the most powerful pushback will come from the planet itself. "There are 195 parties here, 196 with the EU,” said Jean-Pascal van Ypersele, a Belgian climate scientist and until this year vice chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). “But there is one party that is not represented: Nature. It is a party with whom nobody can negotiate.”

An ice sculpture made with Greenland's ice cap by Olafur Eliasson in Paris. December, 2015. (AFP / Joel Saget)

An ice sculpture made with Greenland's ice cap by Olafur Eliasson in Paris. December, 2015. (AFP / Joel Saget)Voices of caution

There were hundreds of scientists at the COP, and many of them sounded alarms as the Agreement took shape. While they applauded the ambitious goal of holding global warming to “well below” 2C, they decried the lack of a detailed roadmap for cutting greenhouse gases.

Just do the math, they said: To have a two-thirds chance of limiting warming to 2C, emissions have to fall 40-70 percent by 2050. To have even a prayer of respecting the 1.5 C target, those mid-century cuts would have to be even deeper: 70 to 95 percent. These are dizzyingly difficult goals which effectively require the total decarbonization of the world economy within four decades. But without these benchmarks – stripped from an earlier draft – the Agreement "does not send a clear signal about the level and timing of emissions cuts," warned Steffen Kallbekken, director of the Centre for International Climate and Energy Policy.

Boosting the ambition of the temperature target on the one hand, while removing the yardsticks against which progress toward that goal could be measured, on the other, is a recipe for failure, he and others said.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)'Not consistent with science'

The day before the Agreement was adopted by all 195 nations under the UNFCCC umbrella, Kallbekken and four other top climate scientists held a standing-room only press conference to comment on the penultimate draft. (The sections they reacted to remained largely unchanged in the final version.)

“I view the current text as weaker than that which came out of Copenhagen. It is not consistent with science,” said Kevin Anderson, Deputy Director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research in Manchester, eliciting gasps from some of the several hundred journalists in the room. All the scientists issues similar cautions, if not quite as dramatically.

Click here to watch on mobile device

Which brings me to the second tell-tale encounter I had during COP21.

A couple of hours later, I ran into Clive Hamilton, an Australian philosopher and author who has written extensively on the topic at hand, including a 2010 volume – “Requiem for a Species” – on why people resist the truth about climate change. He was sitting alone, so I joined him. “I am in emotional turmoil,” Clive said, and I could see he wasn’t joking.

Ten days at the COP had stirred in him a long-extinguished flame of hope that humanity might rise to the occasion after all, and stop global warming in its tracks. This, mind you, from the man who had written off our species. But then, he continued, he heard the scientists, and it suddenly all felt like a chimera. I, too, had been buffeted by the winds of hope and despair, so we compared notes and he wrote a blog post.

Smoke in northern France. February, 2012. (AFP / Philippe Huguen)

Smoke in northern France. February, 2012. (AFP / Philippe Huguen)Focus shifts from problem to solution

From Copenhagen to Paris, the center of gravity on the climate story has shifted from the problem to the solution. Humanity has waited so long to make that transition that the pathway to climate salvation has narrowed to a threadbare tightrope. There are fine-grained blueprints that show it is still possible to hit the 2C target, especially one called the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project. And while there are no silver bullets, a close-to-the-source carbon tax – favored by top scientists, economists and business moguls such as Elon Musk – would make a big difference.

But the margin for error is gone.

Marlowe Hood is AFP's environment and science reporter based in Paris. Follow him on Twitter.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)