Lula, the final battle

Sao Paulo, Brazil -- When I asked the AFP Brazil journalists what they wanted to ask former president Lula, if he finally gave us an interview, I got a surprisingly high number of responses.

Among the correspondents in Rio, Sao Paolo and Brasilia, some wanted to understand why one of the most admired -- and simultaneously one of the most hated -- men in the country was determined to run for president in October, even with his 12-year prison sentence for corruption. In principle, the law should prevent this, even if he was leading in the polls.

Others wanted to know what he would do if he returned to power. And others anticipated self-criticism, their bitterness towards him being proportionate to the immense disappointment that he has provoked in them.

When Paula Ramon, one of our correspondents in Sao Paulo, called to tell me that Lula had agreed to meet with us on the first of March, I told myself that this time would be successful. Not long ago, he had canceled an interview at nearly the last minute.

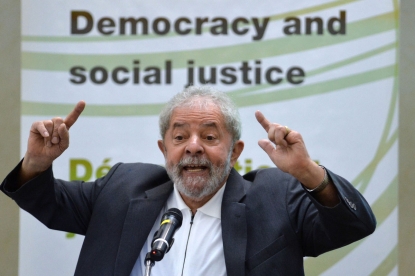

Former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva reacts during a meeting with intellectuals at Oi Casa Grande Theater in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 16, 2018. (AFP / Mauro Pimentel)

Former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva reacts during a meeting with intellectuals at Oi Casa Grande Theater in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on January 16, 2018. (AFP / Mauro Pimentel)I had covered his first term (2003-2007) as an AFP correspondent in Brasilia. I knew that, in difficult times, the man could go radio silent or run from the press, preferring meetings with his supporters. This was the case throughout the “Mensalao” scandal, when his Workers’ Party (PT) was found to have paid bribes in return for parliamentary support.

The affair went to court, several implicated people went to jail, and yet Lula was re-elected, before proclaiming Dilma Rousseff as his successor in 2011. By the time Lula regained his good humor, I had already left Brazil.

Newly sworn-in Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff (L) receives the presidential sash from outgoing President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva at the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, January 1, 2011. (AFP / Evaristo Sa)

Newly sworn-in Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff (L) receives the presidential sash from outgoing President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva at the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, January 1, 2011. (AFP / Evaristo Sa)When I returned to the country -- this time to Rio de Janeiro in 2016 -- the field had changed radically: Congress had just dismissed Rousseff from office. The conservative Michel Temer -- Rousseff’s vice-president, whom she accused of treason -- would take over the last two years of her term. And Lula was in the crosshairs of “Operation Car Wash,” an investigation that uncovered an enormous bribery affair surrounding the state-controlled company Petrobras.

Lula’s schedulers had asked for short CVs from the people who would conduct the interview: Paula, the photographer Nelson Almeida, the video journalist Anne-Laure Desarnauts, and me.

The interview would last for an hour and had only one condition: only the first two questions could be filmed. We’d have to avoid a smooth start, then, because Anne-Laure had to have something consistent for AFP-TV subscribers.

Former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva gestures during a campaign rally to launch his presidential candidacy for the upcoming October elections, at the Workers Central Union (CUT) headquarters in Sao Paulo, Brazil on January 25, 2018.

(AFP / Nelson Almeida)

Former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva gestures during a campaign rally to launch his presidential candidacy for the upcoming October elections, at the Workers Central Union (CUT) headquarters in Sao Paulo, Brazil on January 25, 2018.

(AFP / Nelson Almeida)We wanted to talk to him about three main things: his situation with the electoral courts, which could bar his candidacy, the criminal court, which could send him to prison for the next decade, and finally, his chances of him returning to the Palacio de Planalto in Brasilia.

We were most dreading the anti-elite tirades, which are very practical when it comes to dodging the more delicate questions about his political and personal circumstances.

On Thursday, March 1, I was walking past a newsstand when I saw that the daily paper Folha de S. Paulo had published a long interview with Lula.

I was scared that it marked the start of a PR campaign that would drown out our interview.

Paula Ramon managed to get the interview after months of persistent requests. And now, at a crucial moment, she was out reporting in the Amazonian state of Roraima, 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) from Sao Paulo, and was due to fly back less than two hours before the interview. We were depending on the the weather and the airlines' punctuality. Risky? Sure. But it seemed even riskier to postpone the interview.

I was en route with Anne-Laure and Nelson when my cell phone rang. “I’m in a taxi!” cried Paula. Shortly thereafter, she burst into the Lula Institute, in the traditional Ipiranga neighborhood, with two suitcases in tow.

We entered through the back door, which opened onto a patio with a pool and a barbecue. At the other end was the recording studio.

Three institute technicians prepared their own film setup for the interview. About fifteen minutes later, Lula finally arrived. He wore a red long-sleeved T-shirt under a black jacket, and he greeted us warmly, like old acquaintances. That’s his trademark -- making people he is meeting for the first time feel like old pals. He immediately started talking about the difficulties of governing a country like Brazil, which has over 30 political parties: an “impossible mission.”

Lula, in unexpected ways, led the game. All we could do was ask, “Mr. President, how do you intend then to govern if you return to power?” We ran the risk that he would launch into a long speech about the mysteries of the Brazilian political system.

Paula and I agreed on our strategy ahead of the interview -- she’d ask him questions about corruption in Latin America and I’d ask questions about politics and the economy. Whoever was asking questions would maintain eye contact with him, the other would take notes.

Once the interview began, Anne-Laure began to film, and we were finally able to ask him if he was worried that his judicial troubles would take precedence over the country’s stakes in the electoral campaign.

Workers of the state owned Petrobras greet Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva during a visit to a plant in Canoas, 30 km from Porto Alegre, south of Brazil, 28 July 2005. (AFP / Jefferson Bernardes)

Workers of the state owned Petrobras greet Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva during a visit to a plant in Canoas, 30 km from Porto Alegre, south of Brazil, 28 July 2005. (AFP / Jefferson Bernardes)During the conversation, Lula drank two or three cups of coffee. His husky voice never thundered like it did during the era of the “Mensalao” scandal. He had a calm and focused air, as if nothing were threatening him.

I thought to myself that combat must be a sort of stimulant for him. He seemed to confirm this when he categorically ruled out the possibility of withdrawing from the race in order to avoid increased divisions within the country. “Polarization exists in soccer, religion, politics, and culture. We can’t be afraid of it.” And even less in an electoral campaign where he’s leading in the polls, he added with conviction.

But if battles are his engine, then negotiating and realism are no doubt the former trade unionist’s preferred weapons. Even if this means he has to make agreements that are difficult for the Left to swallow.

“It serves no purpose to look for a saint to make alliances, because...voters are deputies, and we have to discuss with those who have the right to vote. It’s difficult and, at the same time, an exercise rich in democracy,” he explained with the simplicity of someone explaining a theorem.

Soccer, “polarizing” or not, is one of his passions. Lula is a fan of Corinthians, Sao Paulo’s hundred year-old club. He knowledgeably explained different scenarios for the World Cup in Russia. He said he wanted to accompany the Selecao there, but he won’t be able to. “We’re on the campaign trail, and there are no voters over there,” he said.

Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva holds the FIFA World Cup trophy after the officially unveil of Brazil as the 2014 World Cup hosts country, 30 October 2007 at the World football's governing body headquarters in Zurich. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)

Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva holds the FIFA World Cup trophy after the officially unveil of Brazil as the 2014 World Cup hosts country, 30 October 2007 at the World football's governing body headquarters in Zurich. (AFP / Fabrice Coffrini)It’s hard to imagine that this man is going through some of the most difficult moments of a life full of victories, defeats and ambiguities that, for 40 years, were intimately linked with those of Brazil.

The political and judiciary battles are one and the same for him: “My only preoccupation for the moment is proving my innocence. If I’m convicted and imprisoned, then they will be convicting an innocent man.”

But the main thing at stake for Lula is not just his future. It’s how history will view this little shoe-shiner from the Northeast, who became the chief of the huge labor struggles against the military dictatorship at the end of the 1970s and one of the most admired and popular figures on the planet at the start of this century.

“There is one thing that I’m proud of, and that I’m certain is already a part of history: today, in the polls, I am considered the best president in the history of Brazil,” he proclaimed.

“I am the president who founded the most universities...and I will be remembered as the one who started the Zero Hunger program, the greatest social inclusion policy of modern times.”

Brazilian former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva takes part in the seminar Democracy and Social Justice, in Sao Paulo, Brazil on April 25 2016. (AFP / Nelson Almeida)

Brazilian former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva takes part in the seminar Democracy and Social Justice, in Sao Paulo, Brazil on April 25 2016. (AFP / Nelson Almeida)But there’s a part of the Brazilian population that wants Lula to stay in history -- as the first president forced to wear prison clothes. This sentiment is embodied in a puppet, the “pichuleco,” which his opponents wave during protests in support of Operation Car Wash.

A woman walks past "pichulecos," inflatable dolls depicting former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in a prison uniform in Porto Alegre, in the state of Rio de Grande do Sul, Brazil on January 24, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)

A woman walks past "pichulecos," inflatable dolls depicting former Brazilian president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in a prison uniform in Porto Alegre, in the state of Rio de Grande do Sul, Brazil on January 24, 2018. (AFP / Carl De Souza)When Paula asks him if he thinks he could soon be in prison, he responds without hesitation: “Every day.”

But “prison can last a long time, like for Mandela (27 years), or a short time, like for Gandhi.”

I’ve never heard Lula make such a distinction, between short and long prison sentences. I told myself that he must be preparing for the worst, all the while betting on the appeals that his army of lawyers would file if he were convicted, in order to free him quickly and trigger a procedural battle that could be more exhausting for the judges than the unbreakable Lula.

The interview. (AFP photo.)

The interview. (AFP photo.)In the meantime, he’s still campaigning.

As we left, I asked myself what kind of message Lula might have wanted to spread through an interview with an international news agency.

I sensed that Lula wanted to show himself as a wise man with a lot to offer his country and Latin America. His attempt to distance himself from Chavism -- completely new -- without burning bridges with Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, seemed to confirm this.

But to what end? Few people believe in the possibility that he could be eligible, and many predict that he only has a few more weeks of freedom.

His most loyal supporters remember that this is not the first time that Lula has fought against adversity.

But this time, it’s the final battle.

This blog was written with Tori Otten in Paris.

Just elected President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva waves to supporters on October 28, 2002 in Sao Paolo.

(AFP / Daniel Garcia)

Just elected President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva waves to supporters on October 28, 2002 in Sao Paolo.

(AFP / Daniel Garcia)