Learning to recognize PTSD

Paris -- At first glance AFP journalists Patrick Baz and I have little in common. He is an experienced photographer who has covered all of the major conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa over the past 30 years. I have mostly worked in France, with a stint in Tokyo.

Yet we share one thing -- we both suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as a result of our work.

PTSD is a mental health condition triggered by a traumatising event that a person either experiences or witnesses. It can happen immediately afterward, or can occur later, be it weeks, months or even years. To most people, the first thing that comes to mind when hearing PTSD is probably soldiers, because of the things they saw or went through in war. But affects lots of people, like first responders, journalists and can be triggered by a host of things -- an accident, abuse, assault.

A Libyan rebel sits on the back of a pick up truck as rebel forces massed a second day on several kilometres from the key city of Ajdabiya. (AFP / Patrick Baz)

A Libyan rebel sits on the back of a pick up truck as rebel forces massed a second day on several kilometres from the key city of Ajdabiya. (AFP / Patrick Baz)It can manifest itself in a host of ways, including feeling completely powerless, having trouble sleeping and concentrating, engaging in self-destructive behavior like drinking too much, always being on guard for danger, being easily startled, finding oneself detached from loved ones. If not treated, PTSD can disrupt a person’s whole life, affecting his or her work, relationships, increasing risk of other mental health problems like depression, substance abuse, eating and cardiovascular disorders, suicide.

While there have been large strides made toward treating victims of PTSD among the military, among journalists -- who often witness similar things -- the topic still remains relatively taboo.

“The profession is very late in dealing with this issue,” Matthieu Mabin, a reporter for France 24 television, who has created a training center for reporting from dangerous places, told me. “Major reporting assignments were for a long time the reserve of men, who were not expected to admit to suffering of any kind. And women were in a position where they couldn’t say anything either, at the risk of being dismissed as suffering from feminine weakness.”

A US soldier from the 2nd Battallion 12th Field Artillery Regiment, 4-2 SBCT, frisks a man during a night patrol in the town of Baquba, 20 kms northeast of Baghdad, on February 23, 2008. (AFP / Patrick Baz)

A US soldier from the 2nd Battallion 12th Field Artillery Regiment, 4-2 SBCT, frisks a man during a night patrol in the town of Baquba, 20 kms northeast of Baghdad, on February 23, 2008. (AFP / Patrick Baz)You don’t need to partake in an event to get PTSD, sometimes people are affected by witnessing it, like police, first responders and, of course, journalists.

People are evacuated following an attack at the Bataclan concert venue in Paris, on November 13, 2015. (AFP / Kenzo Tribouillard)

People are evacuated following an attack at the Bataclan concert venue in Paris, on November 13, 2015. (AFP / Kenzo Tribouillard)While rates of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders among journalists are “relatively low,” according to the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, there is a “significant minority” who are at risk.

Just a few months ago, I was still unable to admit to myself that I was affected by a mere nine days of covering the aftereffects of the devastating tsunami in Japan in 2011. It was only after I talked about the events with AFP doctor Olivia Hicks, at the urging of a friend, that I finally accepted how much of an impact that coverage six years ago had on me. Before that, I was in denial that, instead of putting the problem in order, just further entrenched it in my mind. “Denial is not a factor of resilience, because the person remains affected by his trauma; it becomes like a scar on the soul,” writes Boris Cyrulnik in his book “Mourir de dire: La honte” (Dying to tell: The shame).

Patrick Baz says that it's probably easier for a reporter of his calibre -- who has covered so many wars and conflicts -- to talk about PTSD. It’s just more expected that people like him, who have covered war, would be affected by it.

Patrick was struck in 2014. He was due to leave for Gaza, but just couldn’t pack his suitcase, which remained open and empty in his house. He wrote an email to colleagues, saying that he would not be going and spent days on his couch, unable to do anything. “It was one assignment too much,” he says. He felt dead in his soul. He would be diagnosed with PTSD later.

For Patrick it was a battle -- “a veritable massacre” -- in Libya in 2011 that he thinks set off the condition.

What made the tsunami an assignment too much for me? Maybe the personal -- as I’m half-Japanese from my Dad’s side, the tragedy hit home. Maybe it was the extreme fear of radiation poisoning that we had after the tsunami set off the accident at the Fukushima nuclear plant. That fear nearly sent me over the edge.

But when I got back to France, I categorically refused to admit that anything was wrong. That denial, along with the fact that I didn’t get any treatment for my symptoms, led to a long medical leave. I remembered a childhood trauma. I thought I was just going through a hard time for personal reasons.

Tsunami aftermath, Sendai, March 13, 2011.

(AFP / Philippe Lopez)

Tsunami aftermath, Sendai, March 13, 2011.

(AFP / Philippe Lopez)Why speak of all this now? After lots of talks with colleagues, friends and psychiatrists, I understood that a journalist who is aware of PTSD and the circumstances under which it can affect him or her is less likely to develop it, and if he does, more likely to get help sooner rather than later. I don’t want others to go through what I went through. And I hope that sharing my experience helps.

AFP’s Dr. Hicks, who is working to develop PTSD prevention methods within AFP, urged Patrick and me to share our experiences. So did AFP management, which is focusing on the problem as well.

AFP has put in several measures to recognise and treat PTSD symptoms. For example, a support manual on debriefing people after assignments has been developed and sent to all regional editors and bureau chiefs. Giving people a chance to speak of what they have seen can both identify someone at risk and get them help as quickly as possible. “Early detection helps to treat and avoid all” of the ills associated with PTSD, as Dr. Hicks explained to me.

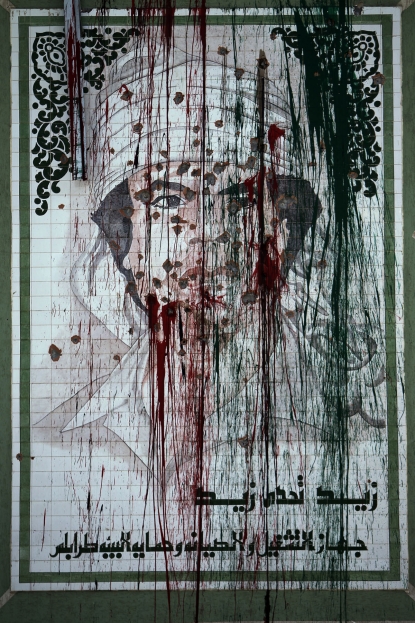

A defaced portrait of fugitive Libyan leader Moamer Kadhafi is pictured in Tripoli on September 1, 2011. (AFP / Patrick Baz)

A defaced portrait of fugitive Libyan leader Moamer Kadhafi is pictured in Tripoli on September 1, 2011. (AFP / Patrick Baz)There are lots of symptoms of PTSD. Patrick found himself often agitated and aggressive and sometimes suffering panic attacks. “I just wasn’t myself,” he says. He underwent Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, a psychotherapy treatment designed to ease the effects and distress associated with traumatic memories.

Other possible treatments include the use of beta blockers, which work by blocking the effects of adrenaline.

Patrick says that in the course of his therapy, he left behind his old self, who got his high covering wars and conflicts. “Before, I was photographing death, today I photograph life,” as he says. Wars “no longer interest me.”

Lebanese groom Tommy kisses the hand of his bride Nadine's while water skiing dressed in their wedding clothes in the waters off the bay of Jounieh, north of Beirut, on May 29, 2017. (AFP / Patrick Baz)

Lebanese groom Tommy kisses the hand of his bride Nadine's while water skiing dressed in their wedding clothes in the waters off the bay of Jounieh, north of Beirut, on May 29, 2017. (AFP / Patrick Baz)For my part, I exhibited many of the same symptoms as Patrick. I drank too much, had successive nights when I couldn’t sleep and just found myself detached from life in general.

All journalists covering a traumatic event will be affected by it. “The trauma is universal,” says Muriel Salmona, a specialist in psychological traumas. “A mass grave is traumatic for everyone.”

But a traumatic event won’t trigger PTSD in everyone. There are various factors involved -- someone may be more susceptible if they went through a childhood trauma, or if they have inherited mental health risks like anxiety and depression, or just in the way their brain regulates chemicals and hormones in response to stress.

Exposure to trauma is a psychological wound. And psychological wounds should not be left untreated any more than physical ones. “Most people would never not treat a fracture,” says Dr. Salmona. “But many people will ignore a psychological trauma.”

A picture taken on March 31, 2017 shows West African migrants returning from Niger after fleeing Libya. (AFP / Issouf Sanogo)

A picture taken on March 31, 2017 shows West African migrants returning from Niger after fleeing Libya. (AFP / Issouf Sanogo)As Patrick says, “If you’re physically injured, it’s considered more noble. But we should not keep up this taboo. People have to understand that there are not only physical wounds. There are also invisible wounds. And I want to make people see them.”

Speaking about your experiences, your wounds, is accepting that you have them, which is necessary for treatment.

Because it took me so long to see and accept the effects covering the tsunami had had on me, I am still not back to 100 percent. I haven’t volunteered to go on any assignments, even though I want to and find myself filled with energy. I have also abandoned video, which is what I was doing when covering the tsunami; preferring today to work in AFP’s multimedia arm. I am still in therapy, trying to digest what I saw.

The whole experience has led to a much better self-awareness. I both know myself better and know my limits. How and where I work as a journalist will be dictated by this acquired self-awareness. I have also become much better at helping and supporting loved ones going through hard times. It’s easier for me, as I have been there.

An Iraqi refugee from Mosul at a camp in the northeast of the country, March, 2017.

(AFP / Delil Souleiman)

An Iraqi refugee from Mosul at a camp in the northeast of the country, March, 2017.

(AFP / Delil Souleiman)