Encounters with Shimon

PARIS -- I’m shown into a cozy room by two secret service agents who ask me to take a seat in an armchair in front of an art deco desk set on a Persian rug. I notice a few trinkets in the room, alongside a few figurines of David Ben Gurion, the founding father of the State of Israel. But what jumps out are some twenty volumes of an old edition of La Recherche du Temps Perdu (Remembrance of Things Past) by Marcel Proust.

Shimon Peres, in whose office I am in, has a reputation for being an avid reader and has been known to write poems in between meetings. He also knows the importance of appearances -- the fact that a work by Proust is prominently displayed ahead of an interview with a French reporter is no accident. He confirms as much when he comes into the room, taking my hand in a firm handshake.

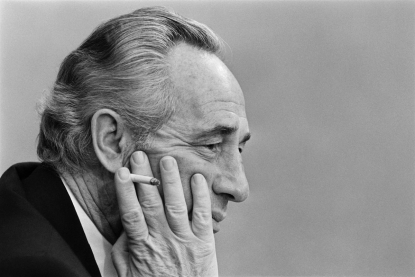

Shimon Peres in his presidential office, April, 2010.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)

Shimon Peres in his presidential office, April, 2010.

(AFP / Menahem Kahana)“Marcel Proust is France,” he tells me.

It’s 1995 and Peres, the consummate Israeli politician, is at the moment the acting prime minister. He speaks in a French that’s heavily accented -- a mix of his mother tongue Polish and Hebrew. Before asking to switch to English, he tells me “France is a bit like a woman whom one loves even if she is unfaithful.” His blue eyes twinkle with mischief.

Relations with France had been an essential part of Peres’s life. So have women, many of whom have not been left indifferent to his deep voice. He is often surrounded by women, even though the only one who has ever counted has been his wife, Sonia. He met her while he was working as a shepherd in the hills between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem.

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart in Paris, 1951.

(AFP / STF)

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart in Paris, 1951.

(AFP / STF)But it’s a picture of another woman -- Lauren Bacall -- on his desk that takes me by surprise. He sees my bewilderment and smiles widely.

“She’s my cousin,” he says. I can’t tell if he’s making fun of me or is serious.

“We have the same name, Perske.” Turns out that Bacall, born Betty Joan Perske whose paternal grandparents came from an area that was once in Poland, is a distant cousin. What a scoop.

We start our interview, which is very relaxed, strangely so. Strangely because three weeks earlier, Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister with whom Peres and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat had shared a Nobel Peace Prize for striking the historic Oslo accords, was assassinated by a Jewish right-wing extremist. Peres, foreign minister at the time, was at Rabin’s side, at a peace rally. Minutes before the shots rang out the two men were singing a peace song along with the crowd.

The pair made for unlikely allies -- for most of their adult lives they were political foes. As I listened to them during that rally, I realized that, aside from their recent conversion that peace was the only way forward with the Palestinians, they had another thing in common. They both couldn’t hold a note. It may not be what history will remember of these two men, but for some reason it is what my ears remember, even today, all those years later.

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (R) and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres wave to a crowd attending a peace rally on November 4, 1995, at the end of which Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish far-right extremist.

(AFP / Sven Nackstrand)

Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (R) and Foreign Minister Shimon Peres wave to a crowd attending a peace rally on November 4, 1995, at the end of which Rabin was assassinated by a Jewish far-right extremist.

(AFP / Sven Nackstrand)Insofar as the rest, they couldn’t have been more different. Rabin was a “sabra,” a native-born Israeli who made his way up the military ranks before entering politics. Peres, an immigrant, had a different way to the top. He began his political career while hitchhiking through the Negev desert one day. Seated in the back of a car that gave him a lift was a small man with white hair and piercing eyes who immediately took to the young man. The elder was David Ben Gurion, the country’s founding father, who was so impressed with Peres during that ride that he made him his personal assistant.

It only made sense that people like Rabin distrusted Peres, who had never served in the military, and were wary of his meteoric rise to political power and the secret missions assigned to him by Ben Gurion. He was nicknamed “the blue jacket,” a derogatory term in an era when Israeli ministers wore sandals and buttoned-down shirts.

Peres in a helicopter flying to Lebanon, November 8, 1984.

(AFP)

Peres in a helicopter flying to Lebanon, November 8, 1984.

(AFP)As we speak during our interview, I remind him of the somber hours that followed Rabin’s assassination. The murder plunged the entire country into shock -- not only because it witnessed for the first time a murder of its leader, but because he was killed by one of its own, a Jewish Israeli far-right extremist.

Later that night I and a handful of other journalists waited in a small room in the basement of the Israeli defense ministry in Tel Aviv. Earlier in the night we had gone to the Ichilov hospital, where Rabin was taken after the assassination and where his spokesman Eytan Haber announced the news to us in a trembling voice. We were then taken to the defense ministry, where we waited for Peres. We were ushered into a small room, with neon lighting and no windows. A long table cut the room in two. Rabin’s photo, a black ribbon on the corner, rested on one of the chairs. The room usually served as a place for top-level security briefings and meetings.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)After a while, Peres entered the room, walking briskly along with a phalanx of nervous secret service agents. I’ve seen him several times before, but never did he appear as pale as that night. The secret service agents were understandably on edge.

Peres whispered something to one of them. He looked like a father trying to reassure his child. He seemed wiser that he had before. Fate has plunged him into a role that he had never managed to get in an election. Sitting, he looked at each of us one by one, remembering who each was, nodding to each slightly. He knew that we were also in shock by what had just happened. For a moment I thought that he may reassure us as well, as he just did with his bodyguards.

After a long silence, he began to speak. His voice was low, full of emotion but determined. His kept his hands on the table, clenched, as if to prevent them from shaking. He said that he will assume the role of interim prime minister, continue the path of Oslo, and move up parliamentary elections by six months.

During our interview, I ask him what was going through his mind as he spoke to us in that basement room.

“Ensure stability. Avoid chaos. Reassure as much as possible. But I was in shock. I am still in shock. Like the rest of the country. It’s the first time that an Israeli leader had been assassinated. We now have our Kennedy. And I am not proud.”

He may not be proud, but he has no trouble wearing his new hat. He had already been prime minister once, in 1976, when he replaced Rabin for three months because the latter had to resign over a foreign bank account. He also served as premier for two years in 1984-1986.

I hesitate for a moment, but then I ask him how he has managed to cope with all those years of being unpopular, of never having won an election, of how he feels now, replacing a man considered as one of the country’s greatest military heroes, killed for having shaken Yasser Arafat’s hand. His face tenses up and I tell myself that our interview is about to be cut short.

Instead he takes a deep breath. “It’s true that I have never been a soldier,” he says. “But there are other ways to fight for your country and they are just as legitimate.”

A member of the Israeli parliament pays his respects in front of Peres's coffin at the Knesset. September 29, 2016.

(AFP / Gali Tibbon)

A member of the Israeli parliament pays his respects in front of Peres's coffin at the Knesset. September 29, 2016.

(AFP / Gali Tibbon)He then lists for me his accomplishments: at 29, the youngest-ever director general of the defense ministry; his negotiations with the French that led to the purchase of all sorts of weapons for the young state; the close relationships that he developed with French politicians that in part led to Paris helping Israelis build a nuclear reactor. It’s an open secret that Israel developed that “reactor” into nuclear weapons, a fact that successive Israeli governments neither confirmed nor denied. When saying the word “reactor,” he once again flashes that mischievous smile.

Shimon Peres in Paris, January, 1981.

(AFP / Georges Gobet)

Shimon Peres in Paris, January, 1981.

(AFP / Georges Gobet)He seems to have completely forgotten that just minutes earlier I had visibly irritated him by saying that he appeared to be more at ease wearing a suit and tie instead of battle gear. It takes more than a comment like that to get under his skin. Just like he did weeks earlier, when people threw tomatoes at him when he visited the Makhane Yehuda market in Jerusalem on a campaign stop.

“I always know how to rebound and land on my feet,” he says.

Disappointment a few minutes after the announcement that Peres had lost the May 1996 election to right-winger Benjamin Netanyahu.

(AFP / Sven Nackstrand)

Disappointment a few minutes after the announcement that Peres had lost the May 1996 election to right-winger Benjamin Netanyahu.

(AFP / Sven Nackstrand)I see that for myself when I meet him again, the next year. This time he is at a new low. It’s a day after May 30, 1996 when Peres -- despite the outrage caused by the assassination of Rabin -- lost the election to a right-wing political animal of another stripe, Benjamin Netanyahu. Noone had expected Netanyahu to win. The defeat is all the more painful as it marked the first direct election of a prime minister in Israel. And it was all the more bitter, as he had already drunk champagne to celebrate his victory, as results had him in the lead for most of the night.

It probably marked the lowest point of his political career. But, as he said, he managed to get up on his feet. Eventually, years later, he would finish his political career as president.

I meet him again in 2007, as I am writing a book on the Iranian nuclear threat. Since he is considered the father of the unconfirmed Israeli nuclear arsenal, it is essential that I talk to him. Smiling the same smile as all those years ago, he tells me, despite the military censor rules, “You know, Israel does not have nuclear weapons. But I hope noone takes the risk of forcing us to resort to using it.”

Over the years, I have met him lots of times. Sometimes they were brief encounters as he left a ministerial meeting, sometimes long conversations in his office. The last was at his Center for Peace in Tel Aviv. From all of them, I remember a man unique in his tenacity, his multiple contradictions and his incorrigible optimism. He didn’t like that word, optimism. “I prefer hope,” he used to say.

When his book “The New Middle East” came out, in which he laid out a vision for reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians, I told him I was skeptical at best. He told me to read it again in order to “work on yourself so you can stay young and optimistic.”

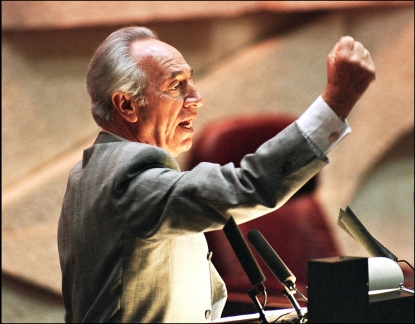

Shimon Peres, then foreign minister, during a Knesset debate on the Oslo accords with the Palestinians, September, 1993.

(AFP / Yoav Lemmer)

Shimon Peres, then foreign minister, during a Knesset debate on the Oslo accords with the Palestinians, September, 1993.

(AFP / Yoav Lemmer)