Covering a trial without paper and pen

DALIAN, China -- I’d started out as a crime and court reporter in Singapore, so I’m fairly familiar with the inside of a courtroom: the solemn atmosphere, the rituals involved, the air conditioning that gives you a slight chill.

So when told I was one of three foreign journalists allowed to attend the retrial of Canadian Robert Lloyd Schellenberg -- more on the case later -- I jumped at the opportunity since it offered a front-row seat to China’s usually ultra-secretive court system.

And what I saw that cold winter day in the northeast port city of Dalian was equal parts fascinating and mind-boggling.

The Dalian Intermediate People's Court, January 14, 2019.

(AFP / Elizabeth Law)

The Dalian Intermediate People's Court, January 14, 2019.

(AFP / Elizabeth Law)First, the rules -- no phones, no cameras, no voice recorders. These were standard rules in most other jurisdictions that I’ve covered.

Then more rules: no paper, no pens, no notebooks… wait what?! It meant I only had my own memory for what was expected to be a long hearing. It was going to be challenging.

Before entering the courthouse on Monday morning, we were again reminded: nothing in your pockets, no electronic devices, no scarves.

Which of course led me to cause a small hold up at security as my snotty tissues, hotel key card and breakfast receipt (those aren't electronic devices!) got pulled out from my coat pockets. A second pat down turned up more tissues and an elastic hair tie I'd forgotten was in my trouser pocket.

Many irritated glares later, my bags had been checked in and I was allowed through -- sans tissue, receipt and hair tie.

Guardian at the gate -- a court security official at the Shanghai Higher People's Court in Shanghai, October 20, 2008.

(AFP / Mark Ralston)

Guardian at the gate -- a court security official at the Shanghai Higher People's Court in Shanghai, October 20, 2008.

(AFP / Mark Ralston)We were ushered up two flights of stairs, across the court lobby and into Court Number 6, a mid-sized fluorescent-lit courtroom. By then, the public benches were nearly full with a mix of what the court said were members of the public.

Then without warning, Schellenberg was brought in -- handcuffed and dressed in a white sweater and black trousers.

Older and more gaunt than in the only picture I’d seen before, his once spiky hair was now a buzz cut, thinning slightly on top. Wearing a pair of black framed glasses, he seemed tense, but was calm for the most part, especially for someone facing the death penalty.

Glimpse inside a China court -- this picture taken and released by the official Weibo account of Yantai Intermediate People's Court on April 7, 2015 shows former Nanjing mayor Ji Jianye (C) standing on trial in a court room of Yantai Intermediate People's Court in Yantai, east China's Shandong province. He was sentenced to 15 years in jail for corruption.

(AFP / HO/Yantai Intermediate People's Court)

Glimpse inside a China court -- this picture taken and released by the official Weibo account of Yantai Intermediate People's Court on April 7, 2015 shows former Nanjing mayor Ji Jianye (C) standing on trial in a court room of Yantai Intermediate People's Court in Yantai, east China's Shandong province. He was sentenced to 15 years in jail for corruption.

(AFP / HO/Yantai Intermediate People's Court)Now a bit about the case: Schellenberg says he visited China for the first time in 2014 as a tourist, making his first port of call the industrial port city of Dalian. This is where accounts differ: he says he got swept up in a drug smuggling ring by Xu Qing, a man he was recommended as a translator. Chinese authorities say he was part of an international drug trafficking syndicate planning to ship some 200 kilogrammes of methamphetamines to Australia.

He had been arrested in December 2014 but the case had plodded along with little international interest until his appeal against an original 15-year sentence was processed last December. This came as tensions were rising between Beijing and Ottawa following the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver on US request.

A TV image provided by CTV to AFP shows Huawei Technologies Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou as she exits the court registry following the bail hearing at British Columbia Superior Courts in Vancouver, British Columbia on December 11, 2018. (AFP / -)

A TV image provided by CTV to AFP shows Huawei Technologies Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou as she exits the court registry following the bail hearing at British Columbia Superior Courts in Vancouver, British Columbia on December 11, 2018. (AFP / -)Suddenly, foreign media were invited to the appeal hearing (AFP was not one) where the Liaoning High Court ordered a retrial, suggesting that Schellenberg be given a tougher sentence given new evidence showing his alleged involvement in the syndicate.

And that retrial took place on that chilly courtroom in early January.

Three judges in their red and black robes took their seats and the court was in session.

A judge listens as case introductions are made inside the courtroom at the Number 1 Intermediate People's Court in Beijing, 25 July 2002. In one of the rare displays of transparency, foreign media were invited to a case on intellectual property rights. (AFP / Frederic Brown)

A judge listens as case introductions are made inside the courtroom at the Number 1 Intermediate People's Court in Beijing, 25 July 2002. In one of the rare displays of transparency, foreign media were invited to a case on intellectual property rights. (AFP / Frederic Brown) A court reporter prepares himself inside the courtroom at the Number 1 Intermediate People's Court in Beijing, 25 July 2002. In a rare display of transparency, foreign media were invited to a case on intellectual property rights. (AFP / Frederic Brown)

A court reporter prepares himself inside the courtroom at the Number 1 Intermediate People's Court in Beijing, 25 July 2002. In a rare display of transparency, foreign media were invited to a case on intellectual property rights. (AFP / Frederic Brown)

The chief judge, a bespectacled woman of indeterminable age, started reading out a series of introductions in a rather sharp voice. I was reminded of Chinese classes where our teacher was a former CCTV presenter with perfect enunciation. Those were not good memories.

After the prosecution made its opening statement, Schellenberg was allowed to address the court, before the floor was given to his defence team.

Speaking in English, which was translated into Mandarin (and vice versa) by two language professors who had been specially brought in to translate the hearing, Schellenberg began to set out his case.

“This is a case about King (Xu Qing), he is an international drug smuggler and a liar,” Schellenberg said, emphasising that he was neither a drug user, nor a smuggler. (Statements which were later proven untrue by Canadian media citing local court records.)

It was a recurring theme that slightly baffled me – the prosecutors having their say, Schellenberg being offered the floor, before the defence lawyers had their turn. Why would one be so involved in court proceedings when there are instructed lawyers?

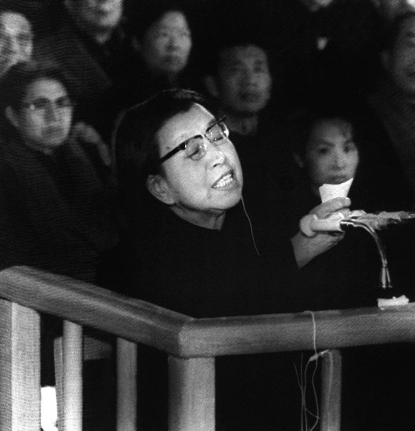

Jiang Qing, one of the defendants of the "gang of four" and late President Mao Zedong's widow, answers questions by the Supreme Court in Beijing during her trial, December 29, 1980. (AFP / Xinhua)

Jiang Qing, one of the defendants of the "gang of four" and late President Mao Zedong's widow, answers questions by the Supreme Court in Beijing during her trial, December 29, 1980. (AFP / Xinhua) A general view of the "gang of four" trial on November 22, 1980 in Beijing. Mao Zedong's widow Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao received death sentences that were later commuted to life imprisonment, while Wang Hongwen and Yao Wenyuan were given life and twenty years in prison, respectively. They were all later released. (AFP / Stf/Xinhua )

A general view of the "gang of four" trial on November 22, 1980 in Beijing. Mao Zedong's widow Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao received death sentences that were later commuted to life imprisonment, while Wang Hongwen and Yao Wenyuan were given life and twenty years in prison, respectively. They were all later released. (AFP / Stf/Xinhua )

Then came the scoldings: the defence lawyers for repeating questions, the prosecution for cutting off Schellenberg, Schellenberg for going off on a tangent… By now the Chinese class resemblance was giving me a feeling of dread in my stomach.

In most court cases I’ve covered, lawyers would have a basic line of questioning, sometimes asking the same question different ways, or even setting up a question in a logical manner. They were allowed to take as long as they needed, especially if the case was a complex one.

But in Dalian, the prosecutor’s questions were pointed and seemingly unconnected.

Questions for Xu, the only witness, jumped from where he had taken Schellenberg on a particular day, to one about the use of a BlackBerry mobile device.

Schellenberg was allowed to question the witness too. I particularly remember him asking about 180,000 yuan ($26,000) Xu had given him.

Without turning to look, Xu simply said to refer to his written statement, a phrase oft repeated during the hearing.

The defence lawyers were told off for asking questions that had already been raised, and for asking the same question in a different manner. And for repeating themselves. It was a curious experience.

A Chinese policeman guards a 28-year-old man suspected of stealing several items from the Forbidden City, in a rare theft at China's ancient imperial palace, during his trial in Beijing on February 17, 2012. According to police records, only four thefts have been recorded at the Forbidden City between 1949 and 1987. (AFP / Str)

A Chinese policeman guards a 28-year-old man suspected of stealing several items from the Forbidden City, in a rare theft at China's ancient imperial palace, during his trial in Beijing on February 17, 2012. According to police records, only four thefts have been recorded at the Forbidden City between 1949 and 1987. (AFP / Str)After the witness was released came evidence time. The prosecution came prepared with Powerpoint presentations. Slides and slides of evidence, helpfully flashed on two screens for all to see.

But this wasn’t enough for members of the public, who were seen openly napping when the hearing got technical. Many took frequent toilet breaks too, though they always came back.

Then it was time for a segment called “the debate”, where both sides argued over points of law, putting our Chinese and legal knowledge to the test. A dull ache was starting to form in my temples.

Throughout all of this, I was desperately trying to remember every detail. In the absence of a notebook, I’d taken to tracing out words on my thigh.

Court staff arrive at the Intermediate People's Court in Jinan, Shandong Province on July 25, 2013. (AFP / Mark Ralston)

Court staff arrive at the Intermediate People's Court in Jinan, Shandong Province on July 25, 2013. (AFP / Mark Ralston)And just as suddenly as it started, it was over. Schellenberg was allowed to make a final statement and the court adjourned for dinner. We were told to come back in an hour at 8pm. The judges were ready to hand down a verdict.

When the session restarted, the chief judge read out her comments.

“Find guilty”, “reject the defendant’s explanation and defence”, “key member of international drug smuggling syndicate”.

Then we were all told to stand.

“In accordance with the laws of the PRC... you are hereby sentenced to death.”

A hush fell over the courtroom. The was a pregnant pause before one of the two translators collected herself to translate. And then it was over.

An Amnesty International report on the death penalty, April 10, 2017, presented at the foreign correspondent club in Hong Kong.

(AFP / Anthony Wallace)

An Amnesty International report on the death penalty, April 10, 2017, presented at the foreign correspondent club in Hong Kong.

(AFP / Anthony Wallace)Schellenberg seemed to handle it well. Asked if he understand what the verdict meant, he nodded.

I couldn’t see his face from my position in the back (everyone was still standing) but he seemed collected. There wasn’t a slump in the shoulders I’d seen in many other cases. Just quiet acceptance.

And that was that. He was told of his avenues of appeal and before I could catch my breath, court was adjourned and everyone rushed for the door -- the public that couldn’t wait to get out after a long long day, the other journalists and I rushing for our phones to break the news.

“Hello? It’s death,” I say quickly to my news editor, Laurent -- so began one of the most surreal phone calls of my life.

It was the second time I had seen the death sentence handed down in court, and it wasn’t any easier than the first. Hours later, after the stories had been sent and the videos (painfully) transmitted over crawling internet, I wondered what it must be like to have to know you’ll possibly never see your family again. That the last of your days will be lived within four walls. In an unknown land whose language you don’t speak.

There are no easy answers to these questions. But with Schellenberg planning to appeal, perhaps a second look at the system might offer more clarity -- unless the authorities decide that reporters have seen enough of what happens behind closed doors in a Chinese courtroom.

Plainclothes police officers gesture at photographers not to take pictures in front of the Number 2 Intermediate Court in Tianjin on December 26, 2018, where the trial of human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang was set to begin.

(AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)

Plainclothes police officers gesture at photographers not to take pictures in front of the Number 2 Intermediate Court in Tianjin on December 26, 2018, where the trial of human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang was set to begin.

(AFP / Nicolas Asfouri)