At 97, matador at heart, journalist by trade

MEXICO CITY, October 30, 2015 -- There is a journalist at AFP who has donned a matador robe and confronted the feared beasts in the ring. His name is Ernesto Navarrete y Salazar, also known as Don Neto.

At 97, he is a living legend –- having covered bullfighting for more than seven decades, there is little he doesn't know about the tradition. He he has worked through 21 Mexican presidents, 17 US presidents and 14 AFP bureau chiefs. He is AFP’s oldest working journalist and likely one of the oldest working journalists in the world. And he shows no sign of laying down his pen.

Don Neto has covered bullfighting as a journalist since 1939, including at Mexico City's "Plaza Mexico" arena, where this bullfight took place in January, 1999. (AFP/Carlos Cazalis)

He was born on November 7, 1918 in Veracruz, on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.

His journalism career began by accident. Or rather because of an accident. In 1939, the young Don Neto was passionate about boxing and bullfighting and was dreaming of a career as a matador. Then a bull gored him, puncturing his stomach in Aguascalientes. “I had to stop for more than a year and my mother told me not to continue.” So, he became a journalist covering bullfighting, first for radio and then for the printed press.

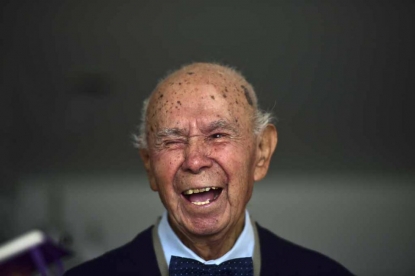

Don Neto. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Don Neto. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)Noone knows exactly when he began working for AFP. He thinks it began around 1943. Old hands at AFP think it was later, in 1959, but can't say for sure.

“The mother of a matador friend sold tacos on a street. One day, I learned that the office of an international news agency called AFP was located on that street. I went there, offering my services to the bureau chief at the time, who accepted. So I started to write stories on bullfighting.”

It was a time when bullfighters were stars in Mexico, a cigar in their mouth and a beautiful woman on their arm when outside the ring, a time when bullfights provoked a lot of passion, but little controversy. At the time, Don Neto was a friend of celebrated bullfighters, like the great Manolete, the Spanish matador who had innumerable triumphs in both Spanish and Mexican rings and whose death by goring in August 1947 Spain marked by three days of mourning.

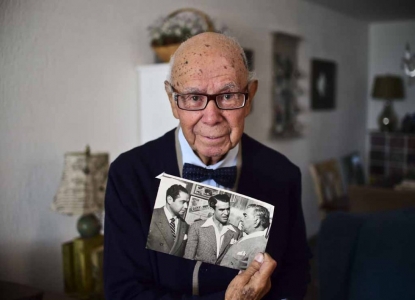

Don Neto has albums stuffed with black and white photographs of the great matadors in which he is often pictured with a microphone in hand, talking to them after the bullfights.

Don Neto (center) interviews bullfighters, with Spain's great Manolete pictured on the left. (Photo courtesy of Don Neto)

He did the first live radio commentary from a bullfight in Seville, taped more than 1,200 radio pieces, and has published an enormous number of news stories. He founded a magazine, taught journalism courses and organized parties and ceremonies for bullfighters attended by top Mexican actresses.

The bullfighters used to come to AFP offices to see Don Neto. One day a bullfighter named Alfredo Leal warned that “If Don Neto doesn’t do the live radio commentary, I’m not participating!” He has interviewed French president Georges Pompidou at the Elysee presidential palace in Paris, who spoke to him about French bullfighting arenas in Nimes.

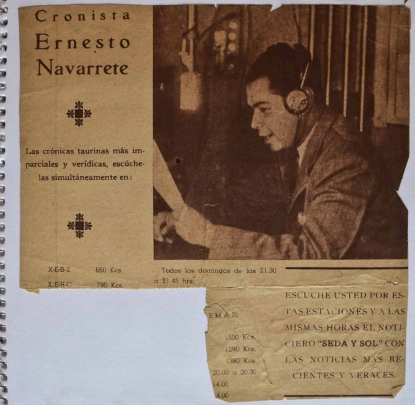

A clipping shows a younger Don Neto during radio commentary of a bullfight. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

A clipping shows a younger Don Neto during radio commentary of a bullfight. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)Today Don Neto is an elegantly-dressed gentleman who lives at his daughter Marta’s house in Puebla, some 130 kilometers from the Mexican capital. The world has changed and so has bullfighting, which has lost some of its luster and adulation. But Don Neto is still here, impatiently awaiting the start of the bullfighting season, curious to see which matadors will step into the arenas and who will perform the best.

Sometimes his daughter takes him to the arenas, but for the most part, he covers the bullfights from in front of his television.

Before the start of the fight, he takes a folding chair from his bedroom, where it lies against the wall, next to a crucifix and a photo of his deceased wife. He looks for his glasses, puts on his headphones, takes a notepad and a black marker. He writes in capital letters the names of the bullfighters, of the bulls, notes the quality of the matadors’ passes and the bravery of the bulls.

Sharp as ever, Don Neto takes notes on the latest bullfight. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Sharp as ever, Don Neto takes notes on the latest bullfight. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)“I turn the sound off, because I don’t want to hear the commentators. I often don’t agree with them. In the past, I’ve had problems with promoters because I say what I see, I tell the truth, I have always wanted to tell the truth and they don’t always like that.”

For him, bullfighting is an art form. “But for that, the bullfighter must have a personality.”

Don Neto gets up from his chair and demonstrates the moves of a matador who fights mechanically, without grace and one whose slow, deliberate motions with his cape are revered by bullfighting enthusiasts as an art form.

“To be a good matador, you need three things – a head, a heart and a stomach. A head to understand the bull and to know how to play him, a heart to have enough courage to do so, and a stomach to be hungry, to want to become a great matador,” he says.

Don Neto explains what makes a good matador. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Don Neto explains what makes a good matador. (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)He writes quickly and then dictates his stories to the Mexico bureau.

“Thanks to him, we were the first ones to give the news in 2010 of a serious accident suffered by the Spanish toreador Jose Tomas in an arena in Aguascalientes,” says Leticia Pineda, an AFP journalist in Mexico. “And then Don Neto followed the entire story. It gave us a huge advantage over our competitors.”

Don Neto is proud to work for an international news agency, to know that his stories are being read from Spain and Portugal to Colombia. “He always gives his AFP business card when introducing himself to people,” says his daughter.

Every once in a while, he visits AFP’s Mexico City bureau in the Roma district. Without fail, he is always courteous and elegantly dressed and has a twinkle in his eye. Sometimes he sheds a tear during these visits, overwhelmed by memories.

Don Neto holds a photo of himself (left) with legendary Mexican bullfighter Luis Procuna (center). (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)

Don Neto holds a photo of himself (left) with legendary Mexican bullfighter Luis Procuna (center). (AFP / Ronaldo Schemidt)Like that of September 19, 1985, when he was at the bureau -- which at the time was on the 28th floor of the Latinoamericana tower -- when a huge earthquake struck, eventually killing between 6,000 and 20,000 people.

“When the shaking began, we took the stairs down. The walls were moving, cracks were appearing in them. When I got downstairs, I saw people praying on their knees.”

The earthquake wiped out the Regis Hotel, where Don Neto once organized grand parties in honor of the country’s matadors, parties that were the place to be.

A collapsed building in Mexico City on September 19, 1985. (AFP / Derrick Ceyrac)

A collapsed building in Mexico City on September 19, 1985. (AFP / Derrick Ceyrac)Don Neto is not just a journalist. He also writes fairy tales that speak of matadors and paints paintings of seascapes, animals and matadors. And he is a dance enthusiast, especially swing. “A seducer, an artist,” his daughter says.

And at the tender age of 97, he shows no inclination to retire as a journalist. As his daughter says: “He couldn’t stop, it’s his whole life.”

Sylvain Estibal is AFP's bureau chief in Mexico. Follow him on Twitter

Mexico City boasts the world's largest bullfighting arena, the "Plaza Mexico," which is shown during celebrations to mark its 60th anniversary in February, 2006. (AFP/Julio Castillo)